Under the baton of Riccardo Chailly, the opening concert of the 2025 Lucerne Festival unfolded as a true aesthetic manifesto: a discreet homage to Boulez, followed by a journey into Mahler’s inner world with « Rückert-Lieder » of sovereign restraint sung by Elīna Garanča, and an orchestral vertigo with the Symphony No. 10, an unfinished ghost in which private grief and cosmic vision intertwine.

Opening Concert – 15 August 2025 (Lucerne Festival)

Lucerne Festival Orchestra

KKL

Conductor: Riccardo Chailly

* Pierre Boulez (1925–2016)

Mémoriale (…explosante-fixe… origineL)

Version for flute and eight instruments (1985, revised 1993)

* Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)

Rückert-Lieder (1901–1902)

Original orchestration and arrangements by Max Puttmann

Mezzo-soprano: Elīna Garanča

* Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 10 in F-sharp major (1910, unfinished)

Completed version by Deryck Cooke (1964, revised 1976)

The Lucerne Festival, now firmly settled into its cruising speed under Riccardo Chailly, remains one of those rare settings where some of the most memorable pages in Mahlerian history were once shaped by the late Claudio Abbado. The opening night of the 2025 edition proved no exception to this vocation: a programme drawn taut as a bow, from the crystalline transparency of Boulez to Mahler’s abyssal vertigo, via the intimate confidences of the Rückert-Lieder, all delivered by a Lucerne Festival Orchestra at the very peak of its art.

Boulez's Incandescent Sparks

Riccardo Chailly first took the floor to pay tribute to one of the pillars of the Lucerne Festival who would have turned 100 this year: the French composer and conductor Pierre Boulez.

To honour his memory, the concert opened with Mémoriale (…explosante-fixe… origineL), a work from 1985 (revised in 1993) for flute and eight instruments. Taken from the vast, tentacular whole of …explosante-fixe…, the piece carries within it a double remembrance: that of a formal quest and of an intimate homage. Dedicated to the flautist Lawrence Beauregard, who died in 1985, it retains his imprint in solo writing of the utmost precision.

Chailly, who has seldom ventured into Boulez’s repertoire, approaches the score here as a miniature of chamber music, shot through with internal resonances. It becomes a prism refracting the material of the parent work. Jacques Zoon, former principal flute of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, deploys a breath that is never mere virtuosity: pianissimo attacks suspended in mid-air, imperceptible multiphonics, trills dissolving like a halo. The spatialisation, observed with almost choreographic care, sends the thematic fragments circulating through the hall, creating that illusion of shifting perspective so characteristic of Boulez.

Boulez’s writing here does not fall into pure pointillism, but into a liquid continuity: seamless transitions built on harmonic glissandi and the most finely calibrated control of dynamics. Chailly ensures this fluid architecture is preserved, where other conductors, more “structuralist” in approach, tend to compartmentalise. The result: seven minutes that condense an entire art of transparency. One is reminded of Karajan’s Webern, in which the post-Romantic continuity was emphasised rather than the radical novelty. There is no Romanticism here in Boulez, but an arresting tableau of sparks emerging from ardent charcoal, black and grey. Every note, every silence is weighed, measured, and yet lived as an organic breath. The flute’s final exhalation, barely perceptible, acts as a suspension before the fall: the homage is complete.

Mahler: the Rückert-Lieder, or the Voice as the Centre of Gravity

The Rückert-Lieder, composed between the summer of 1901 and the summer of 1902, occupy a pivotal place in Mahler’s output: written at a moment when he stepped away from large-scale symphonic cycles to explore a more intimate sphere, they anticipate, through their spareness, the aesthetic transformation of the Kindertotenlieder. The orchestration shifts from song to song, ranging from the most delicate chamber textures (a mere breath of strings and oboe) to a fuller, yet always discreet fabric, designed to let the voice remain the central focus.

Elīna Garanča, with her broad voice and dense middle register, approached the cycle with immaculate German diction and phrasing carved directly from the breath.

The opening Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder! took a lively tempo without any undue haste, the strings delivering crisp attacks, incisive pizzicati lending an ironic edge to Rückert’s text. Chailly adopted a minimalist rubato, allowing the vocal line to rest on the orchestral fabric like a finely drawn arabesque.

Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft became a model of legato, supported by an oboe (Lucas Macías Navarro, one of the evening’s standouts) of exceptional roundness, playing with an almost vibrato-less, spun tone that gave the impression of a suspended fragrance. The balance between winds and lower strings was judged to the millimetre, making every inflection perceptible.

The central, dramatic pivot of the cycle, Um Mitternacht, was shaped without excessive pathos: the build-up to the climax on “Herr über Tod und Leben” was constructed in strictly controlled dynamic tiers. The brass were perfectly layered, the timpani dark but never heavy, lending the conclusion a burnished, brazen gleam that contrasted with the opening restraint.

Liebst du um Schönheit, in Max Puttmann’s rarely heard orchestration, was given a supple, almost Viennese touch: the vocal line retained its natural flow, while Chailly lightened the strings to avoid any saccharine sentimentality, letting the text speak with freshness.

The fifth and final song, Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, holds a unique place in Mahler’s work, not only as the poetic and musical culmination of the cycle, but also as one of the most celebrated pages in his entire output. Often regarded as Mahler’s spiritual self-portrait, it sets Rückert’s deceptively simple poem about a voluntary withdrawal from the world, not from despair, but from a conscious choice to devote oneself to art and contemplation. Sir John Barbirolli famously requested it be performed at his own funeral.

Composed in 1901, as Mahler recovered from serious health troubles, the piece in E-flat major unfolds at a sustained, restrained tempo, its airy textures creating an atmosphere of suspension, as though time itself were dissolving. The long, flowing vocal line unfurls like an unbroken breath. The orchestration is of extraordinary delicacy: no grand gestures, no excess, only a miraculous transparency of timbre.

Here, the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, under Riccardo Chailly, reached a peak of orchestral craftsmanship. The two oboists (Lucas Macías Navarro and Miriam Pastor) offered a dialogue of almost unreal purity: each inflection breathed, supported, and commented upon the voice. Far from a mere accompaniment, their lines became echoes of the soul, extensions of the vocal line itself.

It is easy to see why this final song has become the summit of Mahlerian Lied: its ability to dissolve the boundary between orchestra and voice, to reach a simplicity that borders on the absolute. This evening’s performance captured all its inhabited stillness, ending with a triple piano that faded like an autumnal smile. In that ultimate transparency, voice and instruments seemed to vanish into silence. A moving confirmation that sometimes, the greatest cry of art is a whisper.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 – The Unfinished Phantom

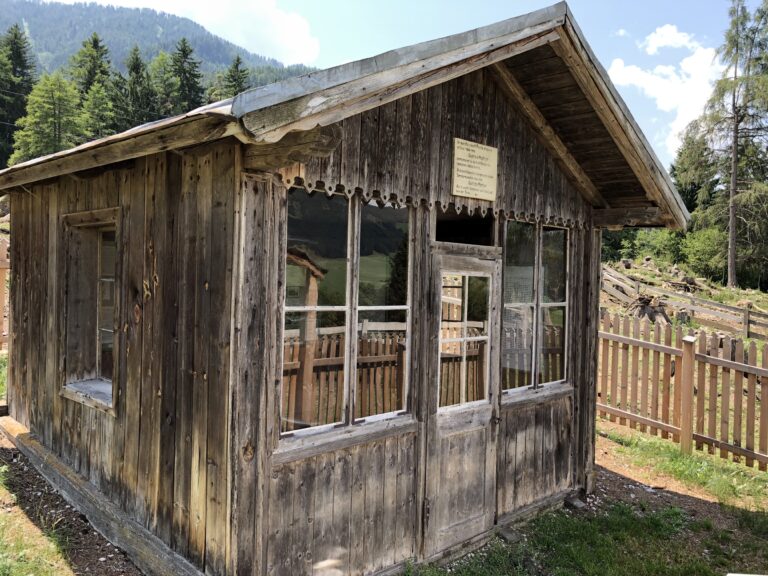

Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 belongs to that rare category of works haunted by the shadow of their own incompleteness, each public performance reigniting a controversy that has never truly been settled. In July 1910, Mahler was working on the symphony at his summer retreat in Toblach, already weakened by illness and shaken by the discovery of his wife Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius. This intimate drama, set against the composer’s acute awareness of his approaching end, permeates the sketches of the score. By September, Mahler left Toblach with the symphony still unfinished: only the first movement, the Adagio, existed in a complete orchestral draft, while the remaining four movements survived as sketches of varying detail. Eight months later, in May 1911, he died in Vienna, leaving behind this incomplete manuscript: a true musical testament.

At first, Alma Mahler locked away the manuscripts. She eventually entrusted the Adagio to her son-in-law Ernst Křenek, who prepared an edition allowing Franz Schalk to conduct its premiere in 1924. The rest of the symphony remained in sketch form, with Alma resolutely refusing any attempt at completion. She maintained that no foreign hand should intrude upon her husband’s musical thought, while admitting that the surviving materials hinted at a coherent and entirely conceivable architecture.

The turning point came in the 1960s with the tireless work of British musicologist and conductor Deryck Cooke. Convinced that Mahler’s surviving drafts contained ample information (full melodic lines, counterpoint, partial orchestration, precise dynamic and articulation markings) to reconstruct the symphony in full, Cooke produced his first “concert version.” Premiered in London in 1964 under Berthold Goldschmidt, it immediately sparked debate: was this genuine Mahler, or a betrayal? Alma Mahler, initially opposed, finally gave her consent in 1963, just before the premiere. Yet many conductors, often composers themselves (Boulez and Bernstein among them) have refused to conduct Cooke’s version, insisting that incompletion is part of the work’s history and cannot be artificially mended.

Thus, every performance of the Tenth in its complete form poses the same question: are we hearing Mahler, or Mahler refracted through the prism of an editor? The tension between philological fidelity and the desire to let the music live forms the inevitable backdrop to any such performance, the spectral presence of the original Adagio looming over the four subsequent movements like a constant reminder of the gulf between sketch and finished work. Riccardo Chailly has never shied away from conducting this score – indeed, he has left a fascinating recording with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra for Decca – but on this night, transformed by an orchestra of breathtaking refinement, he delivered a vision of the work that felt both total and definitive.

On edge: such is how one might sum up the opening bars of this Adagio. Chailly suspends time, stretches the pulse, but not like Rattle (too slow in Berlin): he allows silences that are not mere breaths but genuine apnoeas, as if the orchestra hesitated to enter this dangerous territory. In this initial restraint, one hears the same irregular heartbeats that already haunt the Ninth Symphony, those uneven pulses that seem to foreshadow an imminent end. To consider this Adagio as the logical, inevitable continuation of the Ninth takes but a step: Mahler, on the brink of the abyss, here prolongs his swan song.

The opening orchestral phrases are unstable, halting, as if the music itself were limping, struggling in a space it knows to be doomed. Something approaches – a dread one senses but refuses to face. The image that comes to mind is that of a cloudy mirror. The strings’ piercing high notes, razor-sharp, send shivers: blades of light slicing through the orchestral fabric, heralding the tear.

Is it the music itself that contemplates itself in abyss, observing its own fissures and inner dissonances, as if watching itself die? Chailly, like Abbado before him, achieves that improbable synthesis between lucid analysis and lyrical narration, between a structuralist gaze and a romantic breath. The orchestral matter gradually disintegrates: the music collapses in on itself, like Mahler the man, tormented by conjugal upheavals.

Even the sarcasm – those sudden trumpet outbursts, like a sardonic smile on a ravaged face – takes on an oddly singing quality. But it is the violins that lead the dance: they tell the tale, bearing witness, powerless, to a disaster about to unfold. In the taut dialogue between the left and right desks, one might hear a scene from conjugal life à la Stefan Zweig: on the left, Alma, imploring; on the right, Gustav, in despair. “I am dying.” (No, it’s nothing, everything is fine.)

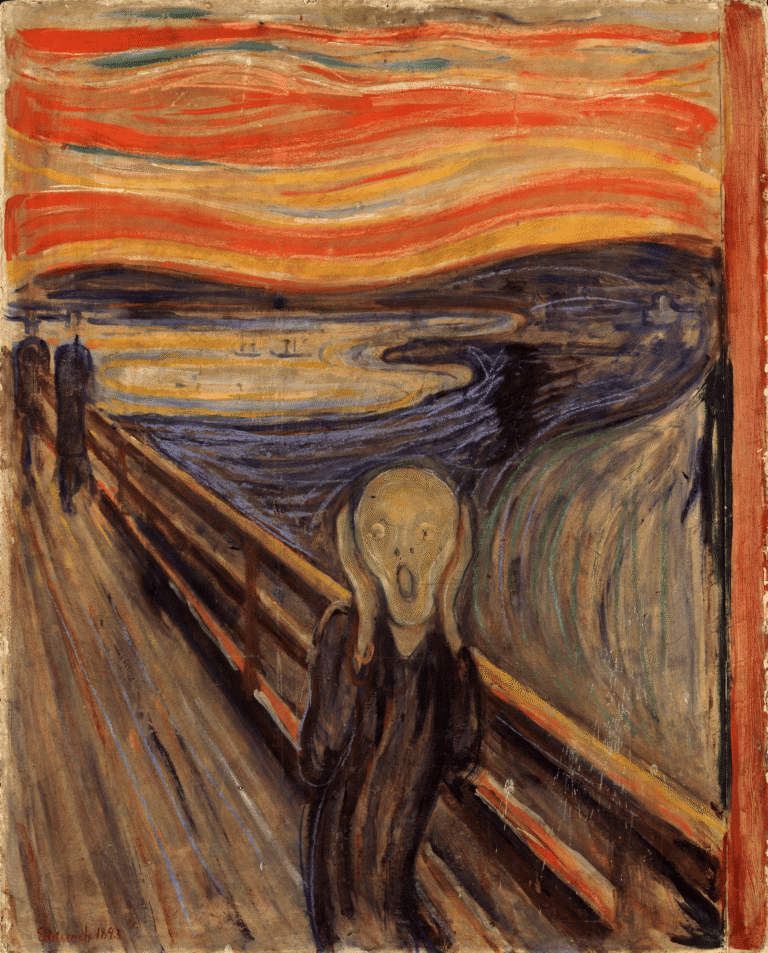

Then comes the triple forte: a frozen sound block, an icy draught from the void, that pierces and wrenches tears. This, surely, is Munch’s Scream, unleashed by the entire orchestra, a cry on the very limits of the audible and the bearable, all the more terrifying for it. And even if, in the final bars, the music tries to reassure in half-voice (as if to say “everything is under control”), the damage is done. It is a farewell: to life, to love, to music itself.

In the Scherzo, the storm breaks immediately, without preamble: an almost Dantesque onslaught, the orchestra stirred like some gigantic machine of creaking mockery. Here, everything is at once dance and caricature, as though Mahler were looking back at his life with a mixture of cruel irony and rending nostalgia. Chailly, in full sympathy with this language, turns it into a shifting theatre, conducting each section like a character in this sonic autobiography.

It is a waltz… or rather its distorted double. Beneath its playful guise, the rhythm is a ruse, a mask concealing a wound. The very setting of the concert, in Lucerne, cannot fail to recall Dobbiaco and the Dolomites, where Mahler composed his final works: the music bears that mountain light, those wide green meadows, the shifting reflections on the lakes, the transparency of alpine air. Yet behind this pastoral vision, a shadow runs: the joy is only apparent.

At moments, the pulse takes on the guise of a Brucknerian Ländler, with that rustic bonhomie which, in Mahler, is never innocent. Some figures grow heavier, as though weighed down by an invisible burden, punctuated by incisive horn calls. The oboe, with an almost celestial clarity, hovers above the tumult, uttering melodic fragments from another world, fragile against the surrounding roughness.

Then, without warning, the waltz hurtles forward: a headlong rush, the vertigo of a dance accelerating toward a breaking point. The strings, razor-sharp, carve diagonal lines like gusts of wind in the mountain passes, while the brass hammer out brazen warnings. Chailly maintains the tension to the end, refusing any escape: this mountain offers no refuge, only ascent, slope, short breath, until the music halts abruptly, as if felled mid-stride.

After the second movement’s deluge, the third (Purgatorio) surprises with its apparent lightness. Mahler here adopts a chamber-like writing, an extremely fine sonic fabric, every timbre chiselled like a miniature. Chailly underlines its precision with exemplary suppleness, giving this page a vivid, transparent sheen.

The flute, in the impeccable hands of Jacques Zoon, soars over the whole with a limpidity that seizes the ear at once: clear lines, flawless articulation, perfectly controlled breath. Navarro’s oboe, equally remarkable, asserts itself as a guiding thread, a discreet yet constant symbol of that inner voice Mahler so often reserves for the invisible heart.

The trumpets enter brilliantly, sometimes incisive, sometimes rounder, like brief shafts of light piercing the chamber fabric. Chailly plays with contrasts: in one instant, the music has the lightness of an intimate conversation; the next, it bursts into an almost thunderous splendour, as though an entire world had invaded the drawing room.

As the piece draws to a close, the lines grow yet finer, more distilled, until the delicate resonance of the harp emerges. The gong, discreet yet solemn, seals the ending in an enigmatic suspension: a sound that seems to float long after the orchestra has fallen silent, like a premonition of what is to come.

The fourth movement, another Scherzo, picks up the narrative thread of the Adagio, as though plunging again into the most intimate pages of a diary. Chailly renders each inflection, each accent, perfectly legible: the tensions, the outpourings, the suddenly broken impulses. This is conjugal theatre in the open air, where we find the violins’ shrill high notes, obstinate, obsessive. With his left hand drawing arabesques, the conductor literally sketches circles in the air, delighting in underlining this tragic circularity that spins on itself, without exit.

In this dramatic round, Reinhold Friedrich’s trumpet asserts itself as a pure blaze: sovereign tone, flawless projection, phrasing that vibrates with the memory of great Mahlerian solos. It echoes the Fifth Symphony: that same ardent nobility, sometimes veiled by a mute, sometimes hard and metallic like a blade. The percussion, dry, almost brutal, lends the movement a physical tension. It is by far the most dynamic, most contrasted page: explosions and whispers, solids and voids, unprecedented textures, colours unheard until now.

Without the slightest break, this tumult tilts into the fifth movement. The bass drum leads the way, ghostlike, like a reminiscence of the blows of fate in the Sixth Symphony (here drawn out to infinity, inhabiting every silence). The low strings, led by the double basses, attack the air with their bows as if to lacerate the sonic fabric, establishing a diffuse, immobile, almost liturgical threat. In this suspended space, one hears an inner cry: “My God, why have You forsaken me?”

Then comes revolt, sudden and violent. Yet the solo flute, clear, almost fragile, opens another path: that of acceptance, of the gaze turned toward what is lost. It sings of days gone by, a farewell song without pathos, of heart-rending modesty. The space widens, revealing bare, glacial peaks, in air so rarefied it merges with silence.

In the last minutes, the dissonance from the first movement returns like a faithful shadow, but transfigured. The Adagio’s opening theme is reborn in the horn, now without brilliance, like a memory whispered. “Remember the happy moments,” the music seems to say. Then comes the distillation: regret, time past, appeasement. The conclusion brushes the void, suspended, with distant echoes of the Ninth Symphony’s final movement by Bruckner, echoes already inscribed in Mahler’s own Ninth. But it is clear: as with Bruckner, incompletion here becomes a definitive state (not absence, but enigma). A music that stops at the threshold of eternity, leaving open the question Mahler never closed.

Thus the Tenth Symphony ends in a breath, and it is the silence that gives it its true dimension. It is not a silence of relief, but an inhabited silence – that rare kind Abbado could create in his Lucerne evenings, when dramatic tension dissolved into an almost metaphysical suspension. With Chailly, this silence extends Mahler’s music as a lingering afterglow, still vibrating in the mind. Boulez, for his part, had another way: to cut it off sharply, without pathos, yet with the certainty that everything that needed to be said had been said. This evening, Chailly seemed to unite the two visions: Abbado’s poetic relinquishment and Boulez’s implacable rigour, making of this final breath a space in which one could, as one chose, lose oneself or find oneself.

Mahler’s music has that unique power: to seize one by the throat, then, at the very moment one’s guard is lowered, to plant an ineffable sadness – gentle and cruel at once – in which suffocating beauty lodges. The silence that follows erases nothing: Mahler remains, still and always, even in the very air one breathes. And tonight, in this summer setting, the ghostly presences of Abbado and Boulez hovered over Lucerne, like twin beacons guiding Chailly towards the fulfilment of an interpretation that will long haunt the memory of those who heard it.