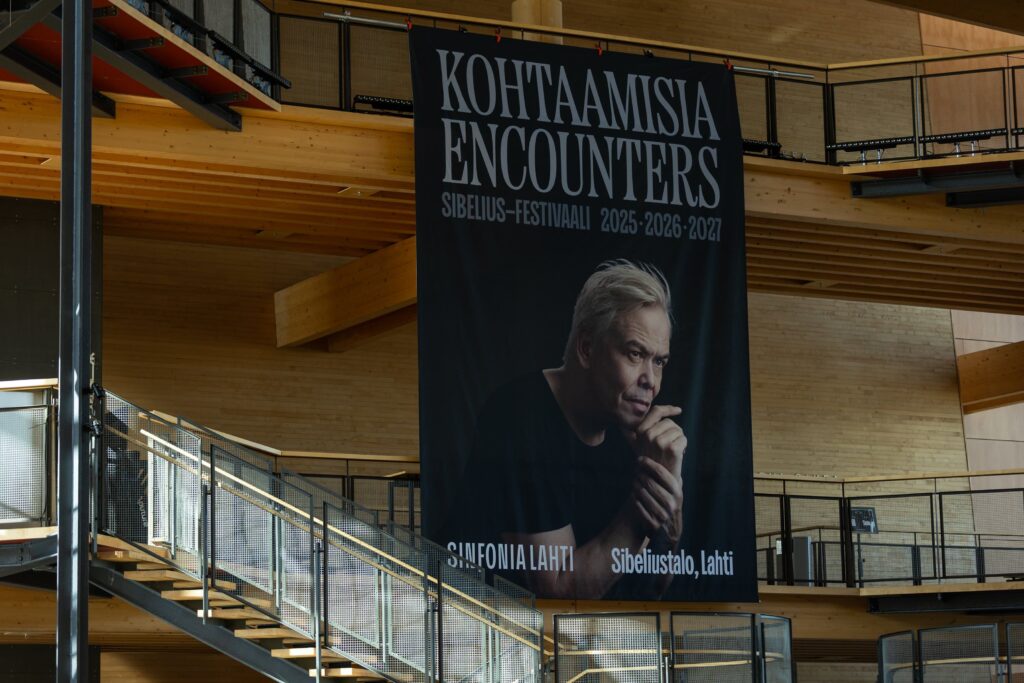

The 2025 Sibelius Festival in Lahti unfolded as a triptych tracing the composer’s early symphonic voice.

Three concerts, three visions of emergence: « Kullervo », « Lemminkäinen », and the « First Symphony », each set in resonant dialogue with Mahler, Wagner, and Grieg.

This year also marked Hannu Lintu’s official debut as chief conductor of Sinfonia Lahti and with it, a bold curatorial statement.

By placing Sibelius’s mythic origins alongside those of late Romantic Europe, the festival shaped a narrative of birth, rupture, and poetic identity.

OPENING CONCERT AUGUST 28th 2025

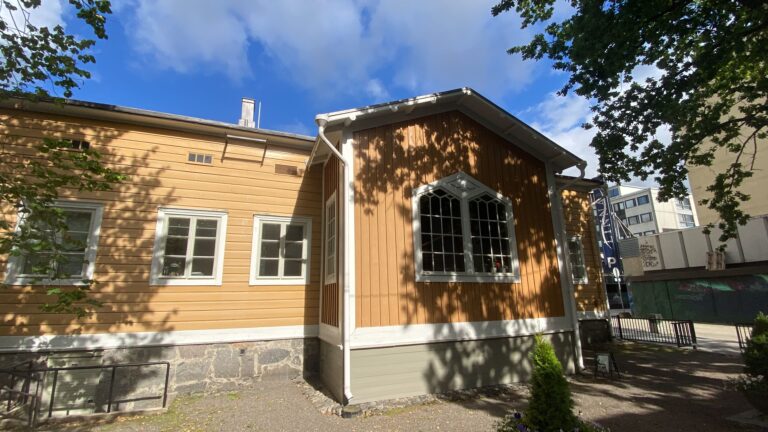

Sibelius Hall, Lahti

Sinfonia Lahti

Conductor: Hannu Lintu

Soprano: Johanna Rusanen

Baritone: Davóne Tines

Choir: YL Male Voice Choir

Programme:

– Gustav Mahler: Todtenfeier (1888)

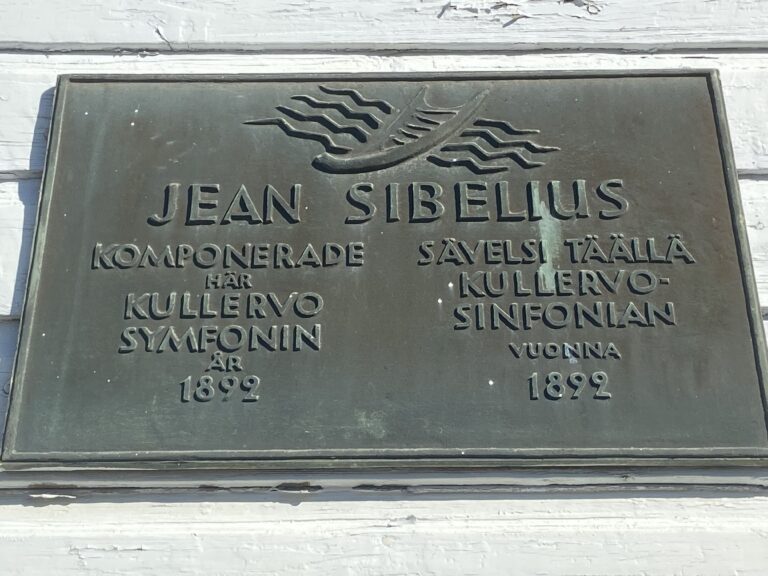

– Jean Sibelius: Kullervo, Op. 7 (1892)

The 26th Lahti Sibelius Festival opened on Thursday, 28 August 2025, marking the 160th anniversary of Jean Sibelius’s birth with a programme of bold “Encounters.” In the Sibelius Hall’s pine-lined acoustics, newly appointed chief conductor Hannu Lintu began his tenure with Sinfonia Lahti, succeeding a prestigious line of Finnish maestros (Osmo Vänskä among them), by pairing Sibelius with an unexpected bedfellow: Gustav Mahler. This opening concert’s concept placed two youthful, death-haunted early works side by side: Mahler’s Todtenfeier (1888) and Sibelius’s Kullervo (1892). The choice embodied the festival’s theme of musical meetings across worlds: as the programme notes observed, both Mahler and Sibelius drew on folk poetry at the dawn of their careers: Mahler on the nature-inspired verses of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Sibelius on the Kalevala, each crafting a first symphonic statement with poetry about death “present from the first bar to the last” . Joining Lintu and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra were soprano Johanna Rusanen, bass-baritone Davóne Tines, and the legendary YL Male Voice Choir, all poised to animate Sibelius’s epic Finnish saga after Mahler’s brooding funeral rite. It was a thoughtfully curated encounter on paper, and in practice it proved a measured, intriguing, if not ultimately incendiary, start to the festival.

Mahler’s Todtenfeier: Funeral Rites Reimagined

Mahler’s Todtenfeier (“Funeral Ceremony”) opened the evening with a visceral atmosphere, its ominous string tremors in the basses immediately evoking Wagner’s Die Walküre. The low strings growled with gravitas and amplitude, summoning the same stormy undercurrent that Mahler, a devoted Wagnerian, likely knew from the opening of Walküre. Lintu ensured the cellos and basses spoke with solemn weight and precise ensemble, setting a scene of foreboding. As the tension rose, the orchestra delivered Mahler’s surging funeral march with clarity and dark lustre. There was admirable polish in the playing: snarling brass and shrieking woodwinds were reined in just enough to keep textures balanced. However, not everything was ideal, a few exposed attacks (a horn call here, a flute entrance there) were slightly imprecise, momentarily unsettling the otherwise solid front. One might chalk it up to early-concert nerves, soon overcome as the performance continued.

Interpretively, Lintu’s reading of Todtenfeier remained clean and controlled, perhaps even too well-behaved for music of such existential angst. Where Mahler’s score can accommodate wild extremes and a febrile, risk-taking pulse, here the journey felt almost too smooth and contained. For listeners intimately familiar with the piece’s later incarnation as the opening movement of the Resurrection Symphony, there was a sense of something held in reserve. Lintu favoured an Apollonian structural overview more than Dionysian abandon, a stance that brought admirable coherence but slightly underplayed the music’s eruptive drama. While this yielded moments of beautiful transparency (the strings’ soft lament was luminous, and the funeral chorale in the brass had noble sheen) one occasionally wished for a touch more fury and vulnerability from the conductor’s baton.

Todtenfeier comes with considerable historical and literary baggage, which Lintu’s measured approach perhaps consciously respected. Mahler composed this single-movement tone poem in 1888, just after finishing his First Symphony (the “Titan”). The title itself nods to an epic poem by Adam Mickiewicz about communing with the dead, and Mahler later admitted that while writing it he imagined his own corpse in a coffin surrounded by wreaths . Indeed, Todtenfeier was Mahler’s first musical grappling with mortality, a fierce funeral march that he initially intended as a standalone piece. It represents the funeral of the fallen hero from his D-major Titan, the composer’s earlier symphony . Mahler imbued it with the existential question of life, death, and what lies beyond: does suffering have meaning, is there life after death? In 1891, when the 31-year-old Mahler played Todtenfeier on the piano for the venerable Hans von Bülow in hopes of approval, the reaction was famously brutal. Bülow covered his ears and exclaimed, “If what I have heard is music, I understand nothing about music!”, even likening Mahler’s work to noise that made Wagner’s Tristan seem as innocuous as a Haydn symphony. This harsh dismissal crushed Mahler’s confidence; he shelved the score and lapsed into three years of creative silence. Only in 1894, after Bülow’s death, did Mahler find a way forward. That year he revised Todtenfeier and folded it into what became his Second Symphony, finding inspiration in a Klopstock resurrection hymn to fashion the choral finale. Todtenfeier thus lives on as the massive first movement of the Resurrection Symphony, music Mahler described as the hero’s life “reflected, as in a clear mirror, from an elevated vantage point” as he is borne to the grave. Knowing this genesis, one appreciates the youthful Mahler’s audacity and the piece’s tempestuous, questioning spirit.

In Lahti, Lintu’s account of Todtenfeier respected its symphonic cohesion and dark sonorities, if not fully its impetuous soul. The climactic moments were powerful yet carefully shaped, the conductor never let the dynamics or tempo run away from him. This led to a closing funeral peroration that was more stately than searing. The final bars, with their grim march rhythm and “spasm of horror” in low strings and percussion, certainly conveyed weight but only a moderate sense of terror. As the last C-minor chords subsided, one admired the Lahti Symphony’s tonal balance and the obvious detailed preparation, even while craving a bit more reckless catharsis. In sum, Todtenfeier here came across as a compelling if somewhat sanitised harbinger of Mahler’s Second Symphony. It was a performance of integrity and intelligence, if not the sort to leave one utterly shaken.

Sibelius’s Kullervo: A Finnish Epic Unfolds

If Mahler’s Todtenfeier is the tormented prologue of a symphonic saga, Sibelius’s Kullervo is a saga unto itself, an expansive five-movement work that straddles symphony, cantata, and tone poem. Premiered in 1892 when Sibelius was 26, Kullervo marked the young composer’s breakthrough, drawing on Finland’s national epic Kalevala to recount a tragic tale of fate, revenge, and ruin. At roughly seventy minutes and requiring a large orchestra, two vocal soloists, and a male chorus, Kullervo is an audacious early creation, brimming with nationalist fervour and Wagnerian ambition. Under Hannu Lintu’s baton, the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and YL Male Voice Choir (joined by Rusanen and Tines) navigated this sprawling opus with commitment. Though the performance at times fell short of truly igniting the work’s epic fire, it offered many passages of great beauty, and showcased some of the orchestra’s finest qualities.

The opening movement (« Kullervo’s Youth ») burst forth with energetic, rhythmically driven playing. Lintu established a firm grip on Sibelius’s distinctive oscillating rhythms; the music’s tread, part march, part dance, had a sure-footed momentum. The strings dug into their figures with vigour, and woodwind interjections were sharply contoured. Notably, the flutes’ staccato motifs had excellent definition, piping up like folk-tale birds punctuating the texture. Lintu shaped the movement in broad, surging waves, showing an ear for Sibelius’s ebb and flow. He made effective use of silences too: several pregnant pauses were held with just enough suspense to keep the audience on edge before the next crescendo. Dynamic gradations were well-judged, from the rumbling timpani rolls in the distance to the full-throttle orchestral climaxes depicting the brash vigor of young Kullervo. If there was a slight reservation, it was that in this movement the orchestra was still finding its warmth, some brass calls and string tone felt a touch on the austere side. But overall, the drive and sweep were present, giving a strong first impression.

In the second movement (« Kullervo’s Journey »), the tone shifted to something more lyrical and atmospheric. Here Lintu struck a fine balance between lyricism and analytical clarity. Sibelius’s scoring in this section can sound episodic, but under Lintu’s direction it unfolded naturally, with each folk-tinged theme emerging and receding like scenes in a cinematic travelogue. The orchestra’s playing turned more nuanced: woodwind lines were delicately phrased, and inner string voices that often get lost were clearly audible, adding richness to the harmony. There was a wonderful subtlety in how Lintu prepared the movement’s climactic moments, one sensed a dramatic foresight, each swell foreshadowed and earned rather than thrown off abruptly. The Lahti players responded with finely shaded dynamics; a gentle melancholy permeated the violins’ songful passages, while the brass outbursts were taut but never overblown. The closing pages were especially memorable: the music dies away as Kullervo’s journey pauses, and Lintu dared to take it down to a true pianissimo. In that rarefied softness, one could hear the hall’s attentive silence, a poetic fadeout that felt like mist settling over a mournful landscape. It’s not often that this movement ends so hauntingly; here the effect was achieved and held beautifully.

The central movement, « Kullervo and His Sister », is the dramatic heart of the work and proved to be the highlight of the evening. It was in this expansive movement that the performance fully hit its stride. The YL Male Voice Choir made its first entrance with a superb presence: their sound was rich, blended, and appropriately stern, truly embodying the role of the Kalevala’s omniscient storyteller. Singing in Finnish, the men of YL projected the narrative with clarity and sonority, from hushed, haunting unisons to the ferocious cries that punctuate Kullervo’s tragic tale. Davóne Tines, as Kullervo, delivered a quite convincing performance. Although his Finnish pronunciation was serviceable if not idiomatic, he portrayed Kullervo with sombre intensity. It is not an easily defining role, more narrative than operatic, and Tines delivered it with gravity if not with an especially distinctive vocal imprint. Opposite him, Johanna Rusanen as the Sister matched Tines with a steely, impassioned soprano. Rusanen’s voice carried over the orchestra with ease, riding the waves of Sibelius’s drama, and she managed to convey the maiden’s initial tenderness and ultimate despair convincingly in her brief but crucial solos. Both soloists maintained a solid partnership, never overpowering the orchestra or choir, but rather meshing into Sibelius’s textural tapestry.

Under Lintu’s direction, the orchestra seemed to warm up fully in this third movement, unleashing a more vibrant palette of sound. The strings found a burnished intensity, and the brass, so slightly restrained earlier, now played with blazing conviction when needed, such as in the chilling chords that mark the sister’s tragic recognition. Woodwind solos (clarinet, bassoon) added poignant commentary, and the male choir’s interjections were electric, especially in the grimly exultant refrain that foreshadows Kullervo’s doom. Lintu paced this long movement very well: he allowed the narrative to unfold with inexorable momentum, yet also gave space for the emotional peaks to register. The rape scene’s orchestral build-up was appropriately terrifying, the music’s savagery delivered without distortion. Conversely, the aftermath, where the sister laments and then disappears, was handled with great sensitivity, the choir’s soft chant and the distant French horn calls evoking an eerie sorrow. By the conclusion of this movement, with the orchestra surging and the choir declaiming Kullervo’s curse, the hall was gripped. It was the sort of cathartic, full-blooded performance that Kullervo demands, and it earned the loudest, most spontaneous applause of the night when the movement finally crashed to its end.

After the monumental third movement, the remaining two movements can sometimes feel epilogic, but here they were given meticulous attention. The fourth movement (« Kullervo Goes to War ») featured some of the evening’s most colourful orchestral playing. Lintu drew out the martial character with crisp rhythms and biting brass fanfares. There was great attention to instrumental colour and detail, one could relish the piccolo and flutes pictoing high above the texture, or the clarinets adding reedy bite to the battle tunes. The Lahti Symphony’s woodwind section shone, each line cleanly etched even in fast, complex passages. The strings too had a bounce and precision, handling Sibelius’s tricky cross-rhythms confidently. As the battle music reached its peak, one couldn’t help noticing a certain Wagnerian echo in the sonic picture: the triumphant brass and rolling timpani had an almost Siegfried-like ring, as if Nordic myth and Teutonic heroism converged for a moment. Lintu seemed aware of this kinship, and he shaped the movement’s ending with broad, bold strokes that indeed conjured Wagnerian sonorities. This movement can sometimes come off as bluster, but in this performance it was robust and exciting without becoming merely bombastic.

The fifth and final movement (« Kullervo’s Death ») was handled with remarkable restraint and emotional insight. Sibelius ends his epic not with a blaze of glory but with a haunted, fatalistic calm, and Lintu respected that. The orchestra opened in hushed, pianissimo mode, strings and woodwinds weaving a dolorous lullaby of death. The atmosphere was that of a funeral lament, distant and mournful. Once again the YL Male Voice Choir entered, and they were impressive to the last, now assuming the role of a Greek chorus guiding the ritual of Kullervo’s self-destruction. Their soft incantatory singing over the light tread of the orchestra was one of the most affecting sounds of the night, full of dignity and pity. Tines and Rusanen do not sing in this finale, it is entirely narrated by the men’s chorus, and the YL choristers delivered the tale of Kullervo’s remorse and suicide with gravitas, never losing tonal focus even at whisper-quiet dynamics. Lintu’s control of these final pages was masterful: he allowed the music to breathe and the silences to deepen, so that Kullervo’s end felt like a true catharsis of sorrow. The very end was not stretched or sentimentalised; it emerged naturally as the culmination of the story. The final chords, bleak and resigned, faded into a long silence before the audience remembered to applaud. It was an emotionally elegiac conclusion, not a triumphant one, fully in keeping with Sibelius’s vision of tragic fate.

As the audience gathered its thoughts at the end of the evening, the conceptual pairing of Mahler and Sibelius undoubtedly gave food for reflection. On paper, the marriage of Todtenfeier and Kullervo made sense: two young composers confronting death through mythic lenses, each work a bold early step toward greater things. In practice, however, the « encounter » between Mahler’s funeral rite and Sibelius’s epic felt more cerebral than visceral. The transition from Central European late-romantic angst to Finnish nationalist legend was intriguing but somewhat jarring; one sensed parallel narratives rather than a true dialogue. The concert as a whole came across as a thoughtful opening statement rather than a white-hot burst of inspiration.

In terms of performance, Hannu Lintu drew solid, often beautiful playing from the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and obtained disciplined, sonorous contributions from the YL Male Voice Choir and soloists. Technically, the concert was a success: ensemble cohesion was generally tight, balances were well-managed, and the tricky acoustics of Sibelius Hall were skilfully navigated. There were many moments to admire: the pellucid woodwind solos that dotted both Mahler and Sibelius’s scores, the burnished warmth of the lower strings, and the thrilling impact of the male choir in Kullervo. These elements stood out as highlights, evidence of a world-class orchestra and collaborators with a deep affinity for this repertoire. Yet, for all its quality, the evening stopped just short of catching fire. Emotionally, Lintu’s interpretations felt a touch reserved. Todtenfeier, especially, never quite unleashed the last ounce of Mahlerian desperation, and in Kullervo some sections (apart from the searing third movement) could have used a bit more wild fervour or Finnish « sisu ». Perhaps the conductor, new in his post and carefully balancing myriad elements, chose to err on the side of control and refinement, an understandable approach, if a somewhat careful one.

In the end, this opening concert fulfilled its role as a ceremonial beginning: it posed questions, paid homage to Sibelius’s legacy and influences, and set the tone for further explorations to come in the festival. It was not a blazing, confrontational meeting of musical minds, but a measured, thought-provoking one. Lintu’s tenure with Sinfonia Lahti thus commenced not with a roar but with an introspective nod, an encounter at the crossroads of two composers’ early visions. As the festival continues, one looks forward to how these initially cautious “encounters” might evolve into more daring dialogues in subsequent concerts. The spark has been lit; now we await the fuller flame…

SYMPHONY CONCERT AUGUST 29th 2025

Sibelius Hall, Lahti

Sinfonia Lahti

Conductor: Hannu Lintu

Soprano: Miina-Liisa Värelä

Tenor: Klaus Florian Vogt

Bass: Ain Anger

Programme:

Jean Sibelius: Lemminkäinen Suite, Op. 22 (1891)

– Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island

– The Swan of Tuonela

– Lemminkäinen in Tuonela

– Lemminkäinen’s Return

Richard Wagner: Die Walküre, Act I (1870)

Suspended Grace and Quiet Irony: Lintu’s Lemminkäinen

On this second evening (29 August 2025) at Sibelius Hall, new chief conductor Hannu Lintu led Sinfonia Lahti in a program that twinned Jean Sibelius’s mythic Lemminkäinen Suite with the first act of Wagner’s Die Walküre. It was a symbolic meeting of Nordic and Central European imaginations. Lintu, in his inaugural year at Lahti, has set out to contextualise Sibelius’s output by juxtapositions such as this, and here the untamed hero of the Finnish Kalevala stood beside Wagner’s world of the Nibelungen. The concert’s second half would bring three star soloists (soprano Miina-Liisa Värelä, tenor Klaus Florian Vogt and bass Ain Anger) to the stage for Walküre, but first came Sibelius’s own epic, rendered by Lintu and the orchestra with evident focus and intent.

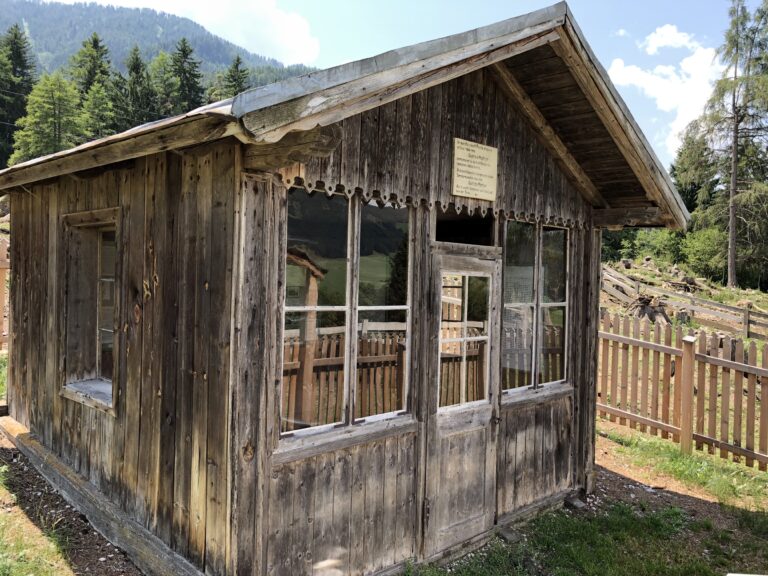

Composed in the early 1890s (and revised in later decades), Sibelius’s four-movement Lemminkäinen Suite is among his most ambitious early works. Often overshadowed by the later symphonies, it is nevertheless utterly central to the composer’s poetic identity. Sibelius originally conceived a grand mythological opera, or perhaps a symphony, based on Finland’s national epic, the Kalevala. That project never materialised, but its spirit lives on in these four tone poems, which together chart the adventures of the Kalevala’s roguish hero Lemminkäinen, a kind of Finnish Don Juan or Siegfried. The cycle moves from seduction to death and resurrection: from earthly revelry to the twilight shores of Tuonela (the land of the dead) and back again. One hears pre-echoes of later Sibelius (even the wintry forests of Tapiola) and occasional Wagnerian hues in the orchestration, yet the musical language is distinctively northern.

« Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island » opened the suite in lush but somewhat cautious fashion. Warm woodwind lines did indeed evoke gentle Nordic landscapes and summer haze, and there were passages of fine, sensitively phrased playing from the strings. Yet the overall effect remained too placid and undercharged, a surprising restraint in music depicting the brash adventures of a warrior seducing an islandful of maidens. One missed the sense of danger, eroticism and narrative drive in this opener; more physicality and abandon would not have gone amiss. Lintu’s interpretation was elegant and clear-textured, but a shade too careful. The climactic revelries never quite caught fire, making this first legend feel more like a pleasant interlude than the start of an epic saga.

If the first movement underplayed its hand, the second proved the revelation of the evening. « The Swan of Tuonela », Sibelius’s most familiar miniature, was here rendered with rare tension, grace and almost preternatural clarity. Principal cellist Aino-Maija Riutamaa de Mata delivered the long-lined cello solos with sovereign ease; her tone was warm, lyrical and queenly, anchoring the music’s mournful dignity. In dialogue with her, Jukka Hirvikangas’s cor anglais sang out with hypnotic, otherworldly purity. Together, these two voices created a floating lament that seemed suspended in time and space. This performance suggested a kind of Finnish pendant to Wagner’s Lohengrin in tone: seraphic, mythic, almost sacred. Under Lintu’s direction, Tuonela became a spiritual borderland. Silence was as significant as sound; soft string murmurs and the dark-hued harp chords formed an aura of hushed reverence. It was music of the in-between, and Lintu’s handling of its contour and pacing showed true mastery. For a few minutes, Sibelius’s tone poem hung like a prayer in the hall, a moment of suspended transcendence that held the audience rapt.

With « Lemminkäinen in Tuonela » (the third movement), Sibelius’s imagination reached its most unorthodox and haunting expression. This section proved the most strikingly original episode of the suite, an abstract, chthonic fresco shimmering with eerie orchestral experimentation. Lintu and the Lahti players conjured a genuinely haunted atmosphere: tremulous string tremolo and low double-bass murmurations suggested a nightmarish forest floor quivering with unseen life. The soundscape recalled the haunted woodlands of Tapiola, though on a more intimate, subterranean scale, less the howling gale, more the whispering shadows underneath ancient trees. On the podium, Lintu’s gestures became almost ritualistic, as if he were Väinämöinen the ancient bard himself, casting a spell of resurrection. The woodwinds’ distant cries had an edge of agony that evoked the ghostly climax of Mahler’s Tenth (stridency transmuted into something spectral and otherworldly). Against this, the upper strings maintained an astonishingly controlled pianissimo, an icy shimmer of violins that never wavered in intonation. Once again the cello and cor anglais emerged to the fore, their plaintive motifs mesmeric in effect, leading the listener through Sibelius’s death-haunted vision. This was an extraordinary meditation on death without a true climax: a depiction of the hero’s lifeless body lying in the underworld, awaiting revival. It ended but with the aching presence of unbeing, the music simply faded into the stillness of Tuonela, leaving a hollow hush in its wake.

The final legend, « Lemminkäinen’s Return », brought a welcome burst of energy, though even here one could have wished for a bit more dramatic grit. It is the most extroverted and brassy panel of the cycle, and Lintu drove it at a lively pace. The orchestra responded with playing that was bold and vividly articulated: jubilant brass fanfares, pounding timpani and swirling strings announced the hero’s homecoming in clear bright colours. There was excitement, to be sure, yet the heroic swagger came across almost as lighthearted rather than truly earthshaking. The performance captured the notes but underplayed the irony, Sibelius’s tongue-in-cheek approach to Lemminkäinen’s macho triumph. At times the buoyant jauntiness, with its quicksilver woodwind runs, even hinted at unexpected echoes of Russian dance music à la Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker. This was unexpected but not unwelcome, emphasizing the playful side of Sibelius’s palette. Lintu kept the momentum tight and buoyant, avoiding bombast. Still, one felt the « return » could have used a touch more bite and wildness: the difference between a triumphant finale and a merely merry one. As a witty end to a predominantly sombre journey, it pleased the ear, but it was perhaps a bit too neat and comfortable to fully convince.

From Kalevala to Valhalla: Mythic Echoes Across the North

The second half of the evening’s programme shifted from the mythic northern landscapes of Sibelius to the tragic operatic drama of Wagner. Without reintroducing Die Walküre in detail, one still felt a resonant kinship between the Kalevala legends of the Lemminkäinen Suite and Wagner’s Norse saga, both explore heroism and fate through music. Concert performances of opera can sometimes feel static, yet this Act I Walküre was unusually compelling: the three soloists fully inhabited their roles, transforming Sibelius Hall into an intimate theatre of gods and mortals. The atmosphere morphed before our ears, what began as a night of Finnish tone-painting became, after the interval, a gripping music drama of love and destiny.

Hannu Lintu proved a veritable magician on the podium, shaping Wagner’s score with electrifying authority. He wielded his baton like a wizard’s wand, conjuring suspense and vivid colour through precise rhythms and gestures. Lintu’s understanding of Wagner is deep and under his direction the orchestra’s sound turned rich and velvety, like a translucent canvas of intentional dynamics. Every tempo was chosen to heighten drama rather than indulge in brute force, and lightning-fast cueing kept energy surging. In Lintu’s hands, Wagner’s music felt freshly minted: he built climaxes patiently and spun out the lyrical moments with an almost incantatory focus, as if casting a spell over players and audience alike.

Tenor Klaus Florian Vogt (Siegmund) delivered a performance of extraordinary lyricism. His voice, often described as a phenomenon in the Wagnerian realm, is lyrical and crystalline, not the usual baritonal Heldentenor. What it may lack in stentorian weight, it makes up in projection and clarity: his uniquely sweet tone carries effortlessly. In this concert he coupled vocal purity with dramatic commitment, every phrase was cleanly floated yet full of urgency. Vogt’s « Winterstürme » was especially ravishing, and one might dub his tender, heart-rending portrayal a « Siegmund Idyll », in playful allusion to Wagner’s famous idyll for Siegfried. It was a Siegmund of poetic nobility, sung with excellent technical command and emotional truth.

Soprano Miina-Liisa Värelä (Sieglinde) matched him with radiant intensity. The Finnish soprano’s voice has ample warmth and a youthful bloom, underpinned by model diction that gave her German text immediacy. From Sieglinde’s first hesitant phrases, Värelä sang with luminous clarity and heartfelt nuance, an ideal approach in the intimate moments of Act I. In the hushed exchanges and the growing ecstasy of recognition, her soprano was both tender and ardent. « Especially in the love duet, her soaring lines and genuine emotion made Sieglinde’s plight painfully real. It was a portrayal of deep feeling and musical refinement, anchoring the sibling-lovers’ bond with vocal warmth.

Bass Ain Anger (Hunding) completed the trio with a performance of formidable menace. The Estonian bass is renowned for his commanding presence and schwarzer Bass timbre, a robust, dark-grained voice that suits Wagner’s villains perfectly . As the antagonistic Hunding, Anger’s tone was cavernous and iron-dark, every word etched in menace. He exuded vocal authority; even in a concert setting he managed to loom dramatically. His phrases rumbled with ominous weight yet never turned coarse, a testament to his technique. Anger underpinned the drama with a gravitas that made Hunding’s presence felt even when silent, drawing an audible tension in the hall whenever he sang. It was a chilling, sonorous performance, giving the love story a truly threatening antagonist.

Notably, Act I of Die Walküre is arguably the most lyrical, almost chamber-music-like episode of the entire Ring cycle. Much of the act unfolds as an intimate three-character interplay with relatively transparent orchestration, and the Sinfonia Lahti rose splendidly to its challenges. Under Lintu’s guidance, the orchestra delivered a warm, glowing backdrop that never overwhelmed the singers, embracing Wagner’s sparse textures and inner detail. One could savour the gentle radiance of the lower strings and the mellow calls of the woodwinds in the score’s softer pages. The playing had a fine-grained control, even at whisper-quiet dynamics the ensemble maintained presence and colour. This chamber-like intimacy drew the listener in, highlighting Wagner’s delicate touches: for instance, at one point a solo cello line entwines with the voices, expressing the love growing up between Siegmund and Sieglinde in a sensuously unified timbre. Such moments, rendered with transparency and care, lent the performance an aura of hushed awe, as if we were eavesdropping on a private destiny unfolding.

Several musical moments stood out as highlights of the evening. In Scene 3, the famous love duet reached a peak of rapture as Siegmund and Sieglinde finally recognize each other as long-lost twins and soulmates. Here Vogt and Värelä’s voices blended in unison with the orchestra’s cello line, a gorgeous, homogeneous sonority that seemed to suspend time. Lintu shaped this passage with great tenderness, drawing silken phrasing from the strings. By the time Sieglinde sings « Du bist der Lenz » (You are the spring) and Siegmund launches into his ardent reply, the music had blossomed into pure sensuality. Immediately following, Siegmund’s love aria, « Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond », was the emotional crown of Act I. Vogt sang this ecstatic spring song with transcendent lyricism, his tenor airy yet impassioned, painting the text about winter’s storms yielding to the joyous May moon. It was deeply moving, beautiful to the point of tears, and one sensed the audience collectively holding its breath during those exquisite lines.

Wagner saved the most visceral punch for the end: the sword revelation. As Siegmund finally pulls the sword Nothung from the ash tree under which it lay embedded, Hannu Lintu unleashed the orchestra in a jubilant eruption. The brass and timpani roared out the Volsung victory motif, the strings surged heroically, an electrifying fortissimo that rang through Sibelius Hall. Vogt crowned it with a fearless top note, and the audience could scarcely contain their excitement. The dramatic high point prompted an immediate eruption of applause and even a spontaneous standing ovation as the last note resounded. In a concert setting this is rare, but it felt entirely natural here: the pent-up excitement demanded release. For a moment, Lahti’s modern concert hall was transformed into Bayreuth, such was the fervour that greeted the Act I conclusion.

In summary, this performance succeeded in turning a simple concert rendition of Walküre into something dramatically alive and emotionally searing. The potential limitations of a non-staged presentation were overcome by the sheer intensity of the interpretation, the detailed orchestral playing, the vivid colours, and the deeply committed singing of all three principals. The visceral impact of Wagner’s drama emerged in full force, standing in bold contrast to the evening’s earlier, more reserved Sibelius piece. What could have been a static run-through became, under Lintu’s spell, a genuine music-theatrical experience. By the end, the cumulative effect of Lintu’s judicious pacing, the singers’ vocal mastery and the overall stylistic coherence cast a powerful enchantment over the audience. It was, in many ways, an unexpected triumph of the Sibelius Festival, one confirmed by the sight of the crowd on its feet, roaring approval for the magic conjured that night under Lintu’s baton.

FINAL CONCERT AUGUST 30th 2025

Sibelius Hall, Lahti

Sinfonia Lahti

Hannu Lintu, conductor

Karita Mattila, soprano

Jean Sibelius: Karelia Suite, Op. 11 (1893)

– Intermezzo

– Ballade

– Alla marcia

Orchestral Songs (Jean Sibelius & Edvard Grieg)

Edvard Grieg

– Solvejgs Vuggevise, Op. 23 No. 2 (D Major)

– Jeg elsker dig (orch. Max Reger), Op. 5 No. 3 (D Major)

– En Svane, Op. 25 No. 2 (F Major)

– Våren, Op. 33 No. 2 (G Major)

Jean Sibelius

– Kevätlaulu (Spring Song), Op. 16

– Illalle (To Evening), Op. 17 No. 6 (orch. Jussi Jalas) F Major

– Arioso, Op. 3 No. 4 A Major

– Våren flyktar hastigt (Spring is Flying), Op. 13 No. 4 E♭ Major

– Svarta rosor (Black Roses), Op. 36 No. 1 C Major

Jean Sibelius: Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 (1899)

– Andante ma non troppo – Allegro energico

– Andante (ma non troppo lento)

– Scherzo (Allegro)

– Finale (Quasi una fantasia)

Karelia's Crisp Charm

The Lahti Symphony Orchestra’s Sibelius Festival 2025 reached its conclusion on 30 August with a final concert drawing a capacity crowd to Lahti’s Sibelius Hall. After two inspired evenings featuring Sibelius’s early epic Kullervo, the mythic Lemminkäinen Suite, and even the operatic drama of Die Walküre Act I, this last night offered a more compact but equally enticing programme. Conductor Hannu Lintu led a slate of Sibelius favourites: the Karelia Suite as a crisp opener, a selection of orchestrated songs by Grieg and Sibelius featuring legendary Finnish soprano Karita Mattila, and finally Sibelius’s Symphony No. 1 in E minor as the grand culmination.

The concert opened with Karelia Suite, delivered in a crisp, almost functional account that nonetheless charmed the audience. In the famous Intermezzo, Lintu slightly reined in the tempo. The march-like rhythms had clear direction and an understated buoyancy, cheerful and festive, if more polite than exuberant. This approach kept the music well-balanced, never rushing headlong, though perhaps at the expense of some visceral thrill. It set a tone of careful cohesion rather than abandon.

The central Ballade emerged as the suite’s emotional core. Here the orchestra’s playing turned warm and lyrical, drawing out the piece’s melancholic shades with tenderness. The cor anglais theme floated sorrowfully, and the strings responded in kind, painting a dusk-lit Nordic landscape. It was beautifully done, yet one couldn’t help recalling Mariss Jansons’ classic Oslo recording of this piece, an interpretation even more ethereal, poetic, and tonally airborne than what we heard in the hall. Lintu’s reading favoured a grounded poignancy over misty nostalgia.

Finally, the closing Alla marcia movement brought a welcome lift in energy. Lintu and his players gave it a jubilant, rousing treatment: bright brass calls, snappy snare drum tattoos, and a confident stride in the orchestra’s gait. It was an effective and spirited conclusion to the suite, earning appreciative applause. While Karelia Suite is never counted among Sibelius’s profound utterances, it was presented here with enough charm and cohesion to satisfy.

From Restraint to Rapture: Mattila’s Nordic Songs

For the evening’s centrepiece, Karita Mattila joined Lintu and the orchestra for a set of orchestrated songs by Grieg and Sibelius, a journey through Nordic lyricism that proved to be the night’s beating heart. Mattila, a seasoned dramatic soprano, managed her vocal resources with intelligence and poise. In the four Grieg songs that opened the set, she sang with artful restraint and crystalline clarity. Each song was lovingly shaped, phrases flowing naturally, yet one sensed Mattila was holding plenty in reserve. The delicate sentiments of these youthful Scandinavian songs were rendered beautifully, if a touch coolly, as though the singer were carefully pacing herself for a long voyage.

Between the Grieg and Sibelius selections, the orchestra offered Sibelius’s Kevätlaulu (Spring Song) without the soprano, a brief interlude that allowed the ensemble to shine on its own. This early Sibelius piece, all gentle swells and vernal atmosphere, was painted in romantic pastel colours. Lintu highlighted its highly atmospheric character: one could almost feel the Nordic spring thaw in the plush strings and the woodwinds’ birdsong-like motifs. It served as a refreshing palate-cleanser and a bridge into Sibelius’s own songs.

As Mattila returned for Sibelius’s songs, she gradually began to unveil the full power and warmth of her voice. In Sibelius’s « Arioso », her middle and upper registers blossomed with golden richness, still under complete control but now filling the hall with a new breadth of expression. Throughout the Sibelius set, Mattila’s presence was arresting, an artist in complete command, projecting warmth and authority in equal measure. Each phrase was weighted with meaning, yet nothing was overdone; she knew exactly how to measure out her gifts.

The emotional arc of this set found its pinnacle in « Svarta rosor » (Black Roses). Here Mattila at last let her voice glow at full intensity, and the result was magnificent. With autumnal tone and long-breathed phrasing, she imbued this song of dark roses and darker feelings with an almost Strauss-like depth, one couldn’t help but hear echoes of the final Four Last Songs in her radiant yet sorrow-tinged timbre. It was an unforgettable performance, steeped in late-Romantic passion and Finnish melancholy, the orchestra providing a shimmering backdrop to Mattila’s soaring lines. Ever generous, Mattila offered an encore,

Ever generous, Mattila offered an encore (« Var det en dröm? », Op. 37 No. 4), which she delivered with bright, heartfelt simplicity, sending the audience into intermission on a high note of admiration and emotion.

Heroism and Heartache in Sibelius’s First Symphony

The concert’s second half featured Sibelius’s Symphony No. 1, a work of youthful fire and searching heart, which here left somewhat mixed impressions. Lintu launched the opening Andante ma non troppo – Allegro energico with a bold sense of drama. The lone clarinet solo at the start was beautifully voiced, full of lonely yearning, before the orchestra swept in to build the first movement’s surging allegro. Under Lintu’s baton the music had a strong propulsive energy and a clear heroic contour, one could discern kinship with the world of Kullervo and the Lemminkäinen legends heard earlier in the festival. The Lahti players responded with vigor: strings biting into their urgent figures, brass and timpani lending a fiery undercurrent. The movement’s climaxes were potent without turning chaotic, and the final bars were delivered with razor-sharp precision, capping an exciting start.

In in the second movement (Andante, ma non troppo lento), Lintu’s interpretative choices proved more controversial. Sibelius marks this soulful interlude ma non troppo lento (not too slow), yet Lintu opted for an unusually slow, almost dreamy tempo. The music unfolded like a wintry reverie, hushed and poetic, indeed, at times it conjured the spirit of Tchaikovsky’s snow-laden reveries… The orchestra played with great sensitivity here, coaxing a hushed, silvered tone from the strings and woodwinds. There were moments of undeniable beauty: a sense of deep stillness and Nordic night. However, at such a leisurely pace the movement’s structure seemed to lose some coherence. The long lines threatened to sag, and the forward momentum nearly froze. Evocative as it was in the moment, this Andante risked dissolving into an ambient haze; one longed for a touch more flow to keep Sibelius’s musical narrative intact.

The Scherzo (Allegro) regained some vitality, though it did not quite match the incisive bite known from some other interpreters. Lintu drove this third movement with a firm hand, the rhythmic foundations were solid enough, yet the execution felt slightly undercharged. The tempo, while brisk, could have been sharper, and the articulation crisper. One missed the last degree of ferocity and precision, the kind of crackling electricity that, say, Osmo Vänskä brought with the same orchestra on disc with his taut approach. Here the Lahti Symphony played cleanly but without that extra demonic gleam in the eye. As a result, the Scherzo’s thrills were tempered, its impact a tad softened, though the quiet, scurrying transition into the finale was handled expertly, suspense hanging in the air.

In the Finale (Quasi una fantasia), Lintu emphasised the music’s dark grandeur and undercurrents of struggle. The movement opened in sombre, shrouded tones, the string chorale like a clouded northern sky, from which the timpani’s heartbeat and the clarinet’s lament emerged again, tying the finale back to the symphony’s beginning. As the movement progressed, unsettled energy simmered beneath the surface, occasionally breaking out in passionate outbursts. This First Symphony often seems to wear three faces: at times the noble Kalevala epic, at times echoing Russian-romantic pathos, and ultimately searching for a new, distinctly Sibelian synthesis. Lintu underscored the work’s tragic, searching qualities most of all. The performance stressed weight and gravity, bringing out Mahlerian shadows as much as Nordic defiance, and one felt the music’s yearning for resolution. Yet at moments the pacing became too weighty, stretching the tension a little thin. The final pages, with their anguished descending scales and abrupt silences, conveyed a powerful sense of unresolved turmoil. The symphony closed not in triumph but in a kind of defiant uncertainty. It was a thought-provoking interpretation, finely played throughout, if not an ultimately cathartic one. As the last E minor chord died away, one couldn’t help but reflect on this dialectical work of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and wonder where Sibelius’s symphonic journey would lead next…

No sooner had the Symphony’s applause subsided than Lintu offered a parting gift: Finlandia as an encore. Taken broadly and grandly, this familiar national showpiece still stirred the soul. The opening was spacious and gravely sonorous, the brass and low strings intoning with almost organ-like majesty. Then came the swell of hope, horns and trumpets ringing out, the timpani driving noble rhythms, answered by the famous hymn theme in lustrous, hymn-like fullness. Lintu shaped Finlandia with loving care for its rhetorical flair and contrast: from hushed reverence to thunderous exhilaration. Even for those who have heard this work countless times, its patriotic ardour proved effective. By the final, blazing bars, the audience was fully overcome, an eruption of applause and a standing ovation crowned not just the encore, but the entire evening.

In retrospect, this closing night of the Sibelius Festival was rich in colour and lyrical generosity, though not uniformly consistent in pacing. The true musical stars of the evening were undoubtedly Karita Mattila, whose profound song interpretations will linger long in memory, and the orchestra’s rousing Finlandia, which sent spirits soaring. By contrast, the Symphony No. 1, while admirably played, left a more ambivalent aftertaste: perhaps a bit too heavy and inward to provide a rousing climax to the festival. As the applause finally faded and people filtered out into the late summer night, one left with the impression not of a grand crescendo, but of a slow-burning epilogue. This was an ending in a reflective, nostalgic vein, an autumnal afterglow rather than a blaze, and in its way, that felt deeply fitting and deeply Finnish. The Sibelius Festival closed on a note of thoughtful reverie, its final chords echoing in the heart.

As one stepped out of Sibelius Hall into the misty evening by the lake, the shifting light and soft drizzle seemed to signal autumn’s quiet arrival. This gentle descent into the season mirrored the emotional arc of the festival itself: an experience at times luminous, at times crepuscular. From the rare grandeur of Kullervo to the haunting beauty of Lemminkäinen, from the electrifying Walküre to the introspective close, the festival offered a journey through myth, voice, and symphonic invention. The second evening glowed brightest: a summit of vocal and orchestral synergy, but throughout, the engagement of the musicians and the thoughtful shaping by Hannu Lintu, in his first year as chief conductor, gave the festival a sense of artistic direction and renewal.

A new chapter has begun in Lahti, one attuned to depth, nuance, and the quiet power of seasonal transformation.