Date and Venue: August, 29th, Sibelius Hall, Lahti (Finland)

Conductor: Dalia STASEVSKA

Orchestra: Lahti Symphony Orchestra (Sinfonia Lahti)

Program:

Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

2.Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43

“For me, the only immortality lies in my music.” – Jean Sibelius

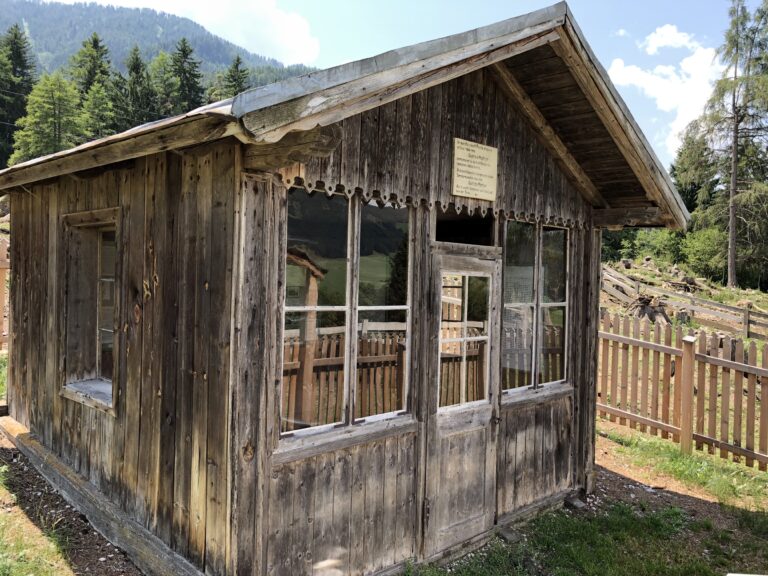

Before diving into the music of Sibelius, it is always enriching for the traveler, the music lover-pilgrim, to visit the composer’s grave at Ainola. Here, one encounters a simple square monument, devoid of any dates, which, much like the black monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey, imposes itself within a landscape where the wind, the leaves, the rustling of nature, and the elements evoke the presence of the god Tapio. This form of pantheism permeates the very veins of quartz in the granite. In this atmosphere, one can truly grasp the essence of Sibelius’s symphonies, rooted in nature, timeless in their structure, and in this sense, profoundly human, alive, and organic.

This year, the Lahti International Sibelius Festival holds a special significance as it celebrates its 25th anniversary. Since its inception, the festival has been dedicated exclusively to the music of Jean Sibelius, offering a profound and singular focus that has drawn listeners from around the globe. On this August 29, 2024, the festival awakens with a unique vibrancy as it embarks on a three-day journey through Sibelius’s complete symphonic cycle. Under the baton of Dalia Stasevska, all seven symphonies will be performed, making this year’s edition a truly remarkable celebration of both the composer’s legacy and the festival’s enduring success.

Over the past quarter-century, the festival has seen the leadership of several illustrious conductors who have shaped its reputation. Figures like Osmo Vänskä, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Okko Kamu, and Sakari Oramo have each left their indelible mark, offering interpretations that have become benchmarks in the appreciation of Sibelius’s music. The Lahti Symphony Orchestra, under these and other conductors, has been the backbone of this festival, bringing to life not just the iconic symphonies but also lesser-known works of Sibelius.

The festival’s singular dedication to Sibelius has ensured that it is not just a showcase of popular works but also a rediscovery of his broader repertoire. Whether it’s the original versions of familiar pieces, such as the 1904 version of the Violin Concerto, or the revival of Sibelius’s stage music, the Lahti Sibelius Festival has continually expanded the appreciation of the composer’s genius.

This year, as the festival commemorates 25 years of pure Sibelius, it does so by honoring the timeless connection between the music and the natural world that inspired it—a connection that every listener, especially those who have made the pilgrimage to Ainola, can deeply resonate with.

Sibelius’s First Symphony: a Song of the Earth?

Sibelius’s First Symphony, composed between 1898 and 1899, is a work deeply entrenched in the late Romantic tradition, yet it already hints at the unique voice that would come to define his later compositions. Premiered in Helsinki in April 1899, this symphony was composed at a time when Finland was under Russian rule, and the growing nationalistic sentiments of the Finnish people were beginning to find their expression through art and music. This symphony, while not overtly programmatic, is often seen as a reflection of Sibelius’s personal and national struggles, blending classical structure with the rich folklore of his homeland.

The opening movement immediately captivates with the slow, almost erratic theme introduced by the clarinet. This languid melody sets a contemplative tone before the strings burst forth, evoking the imagery of a forest rising. It is unmistakably a symphony rooted in Sibelius’s inspirations—the folkloric influence and the epic tales of the Kalevala are palpable. One can almost hear the echoes of Lemminkäinen on his adventures, striving to conquer the world.

Throughout this movement, the atmosphere shifts fluidly from reverie to conquest, then to a more aggressive stance, all interwoven with moments of incredible poetry. A divine harp and a mesmerizing first violin (wonderful Mikaela Palmu) create these ethereal passages that contrast sharply with the forceful dynamics that follow. Dalia Stasevska is clearly intent on showcasing the full breadth of Sibelius’s capabilities in this symphony. It becomes a demonstration of power, with abundant fff markings that roar and resound, often dazzling in their intensity. Yet, Stasevska expertly balances these outbursts with a profound sense of silence, crafting beautiful moments where time seems to suspend.

The second movement could be aptly named Sibelius’s “Winter Dream.” It begins softly, with the charm of a delicately Slavic lullaby, making it impossible not to think of Tchaikovsky. The lightness of the music evokes the feeling of the first snow—gentle, cushioned, and serene. It’s a lullaby of snowflakes, with the playfulness of an elf, that Dalia Stasevska embodies perfectly.

As the movement unfolds, it occasionally transforms into a “Valse Joyeuse,” dancing with happiness. Scattered throughout are echoes of Finlandia; the opening chords of this piece are distinctly recognizable. Is there an internal conflict here between two musical worlds, between Russia and the emergence of a new national identity in music? It seems so. Much like Michelangelo’s Slaves, struggling to free themselves from their blocks of marble, Sibelius’s singular genius attempts to break away from its musical roots and inspirations, forging a new style and a national music. Yet, the lullaby returns, and this beautiful meditative movement continues to stretch and breathe, capturing the listener in its contemplative embrace.

The third movement brings forth a kind of heroic and optimistic agitation. The hero continues his conquest, even his gallop, evoking a resurgence of Romanticism. There are feverish surges, and one can also detect the influence of Bruckner’s scherzos—something earthy, almost agrarian. It feels more like the Finland of fields and hay than that of forests and lakes.

The final movement, which flows seamlessly from the third, broadens the landscape. After the early summer light, we are now in the presence of gray clouds, in a more anxious climate. Here, we return to the epic atmosphere of the Kalevala, with a constant energy that drives the movement forward. It is an interesting piece that reveals the breaks and discontinuities in Sibelius’s musical discourse. A theme, still very Romantic and Slavic, returns like a persistent, perhaps cumbersome, memory. One can sense the hesitations, the jolts, even the frustration, in Sibelius’s creative process as he searches for his own voice.

This movement is deeply telluric, grounded in the earth, with a Romanticism that is fully embraced. As the movement progresses, we are led to an almost shamanic and spellbinding dawn in the final martial chords. The finale asserts itself in a theatrical and tragic magma, bringing the symphony to a powerful close.

Sibelius’s Second Symphony: water world ?

After the elemental exploration of the First Symphony, where Dalia Stasevska seemed deeply attuned to the earth, the subsequent work brought forth an entirely different atmosphere, one marked by water. In what was an astonishing interpretation, this piece felt almost aquatic, with a fluidity and translucence that contrasted starkly with the grounded, earthy nature of its predecessor. The evening’s triumph was particularly embodied in this symphony’s interpretation, which carried a distinct sense of the oceanic.

In 1900, Sibelius returned from a European tour during which his works—The Swan of Tuonela, Finlandia, and Symphony No. 1—were performed at the Paris Exposition Universelle. That same year brought tragedy to his family when his youngest daughter, Kirsti, born in 1898, succumbed to typhus. The loss was a devastating blow, leaving the family in deep mourning. In the early summer of that year, Sibelius received an anonymous letter offering a glimmer of hope during this dark period:

“You have spent enough time idly at home, Mr. Sibelius—now that is enough! It is high time for you to travel. Preferably, you should spend the autumn and winter in Italy. Eternal Italy, a country where one can learn cantabilità, proportions and harmony, the plasticity and symmetry of lines. Here is a grand country where even ugliness strives to be beautiful! You know very well how significant, even decisive, this Italy was for the artistic development of a Richard Strauss or a Tchaikovsky!”

The letter’s author soon made himself known as Baron Axel Carpelan, a passionate Finnish music lover and musician, who had discovered Sibelius’s work at the Paris Exposition. Thanks to Carpelan’s encouragement, Sibelius secured a grant that allowed him to travel to Rapallo, near Genoa, where he stayed with his family in early 1901.

During his time in Italy, Sibelius wrote to his friend Robert Kajanus:

“The Mediterranean in storm! The migratory birds are here! They are being shot at. Traps are set for them. Even poisoned cakes. Yet they sing, waiting for spring. Finland! Finland! Finland! … Do you still love my music? Write. The almond trees are in bloom!” (March 2, 1901, postcard to Robert Kajanus)

In this inspiring Italian landscape, Sibelius began work on his Symphony No. 2. Initially, he envisioned a tone poem centered on Don Juan, likely inspired by the Berlin premiere of Richard Strauss’s Don Juan, which he had attended not long before. However, the concept gradually evolved, transforming into a suite of four tone poems based on characters from Dante’s Divine Comedy. When Baron Carpelan later inquired about his progress, Sibelius replied, “I could, dear friend, introduce you to my work, but I refuse to do so on principle. To me, a musical composition is like a butterfly: the moment you touch it, its essence vanishes. It may still be able to fly, it’s true, but its beauty is no longer the same!”

So, tonight, this wonderful butterfly immediately draws attention with its airy texture. The orchestra, under Stasevska’s direction, delivers a sound that is almost chamber-like in its clarity. Once again, her mastery of silence is on full display, allowing the music to breathe and the spaces between notes to resonate. Sibelius here seems to echo The Oceanides at times, with a liquid shimmer in the strings that evokes the impressionistic touch of Debussy. It’s as if the music dances on the water’s surface, and one is left to wonder whether these are the songs of sirens or nymphs. In Finnish mythology, there are indeed spirits of water known as vesihiisi or ahtis, who could be likened to nymphs, further deepening the aquatic imagery in this interpretation.

The second movement, biographical in nature, stands as a symphony in itself. It begins with the pizzicati of the double basses, soon joined by the cellos, which weave a cantilena, an elegy of sorts. This somber beginning gradually accelerates, leading into more epic, majestic themes. Once again, the silences are remarkable, allowing the music to pause and breathe, before moving into passages that are deeply poignant—at times even resembling a cry. This movement is complex, a world unto itself, far removed from the radiant Italy that one might imagine. It is as though Sibelius is channeling his grief and transforming it into something monumental and deeply personal.

In contrast, the third movement asserts a distinctly Italian character, reminiscent of a lively carnival or saltarello. It evokes the spirit of the Commedia dell’arte, evoking an Italy that was perhaps both dreamed and lived by Sibelius. Following a brief silence, new contrasts emerge, bringing forth echoes of Berlioz’s Roman Carnival. There is a playful, almost whimsical quality to this movement, and Dalia Stasevska, with her light, amused, and relaxed direction, perfectly conveys this sense of joie de vivre. Yet, interspersed throughout are moments that pull us back into the melancholy of the previous movement, creating a fascinating interplay between light and shadow.

The fourth movement marks a return to grand Russian Romanticism, though it remains tempered by fluid strings and remarkable bass lines. The fluidity persists, creating a sense of ebb and flow reminiscent of what I could name « a Finnish Moldau », while moments of ethereal Wagnerian textures and rustlings occasionally foreshadow Tapiola. There is a clear refusal of pathos, leading instead to an energetic conclusion that favors the continuity of the Italian discourse—solar and joyful. This interpretation steers well clear of the syrupy Romanticism that can be found in other renditions.

The ending is both spectacular and contemplative. In the final moments, the high-register violins seem to almost quote the prelude of Lohengrin in their ethereal, supernatural, and divine quality. Here, the quest for the Grail is subtly replaced by the Finnish Sampo—a mythical object of immense power and significance in Finnish mythology. Stasevska’s interpretation conveys this sense of epic grandeur without succumbing to excessive sentimentality, culminating in a triumphant finale. The brass section, in particular, delivers remarkable performances, adding to the movement’s sense of triumph and grandeur, and their efforts were rightfully rewarded with a standing ovation.

This opening concert sets the stage for a festival that promises to unfold under the best auspices. The evening was a resounding success, a testament to the strength of the program and the excellence of the performers. With such a strong start, the Sibelius Festival seems poised to offer a series of unforgettable performances, making this one of the most promising editions in recent years.