At the Lucerne Festival, Kirill Petrenko and the Berlin Philharmonic delivered a performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony as unrelenting as it was vertiginous. No tears, no patho, only an architecture of oblivion, hewn from shadow and fire. The conductor, with surgical precision, summoned a radical vision: dry, chiselled, stripped of all emotional indulgence. The audience, gripped by the throat, remained frozen until the final silence. A lesson in lucidity. A lightning strike without a sound.

Lucerne Festival – Wednesday 3 September 2025

Kultur und Kongresszentrum Luzern (KKL)

Berliner Philharmoniker

Conductor: Kirill Petrenko

Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 9 in D major

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony: A Visionary Farewell Song

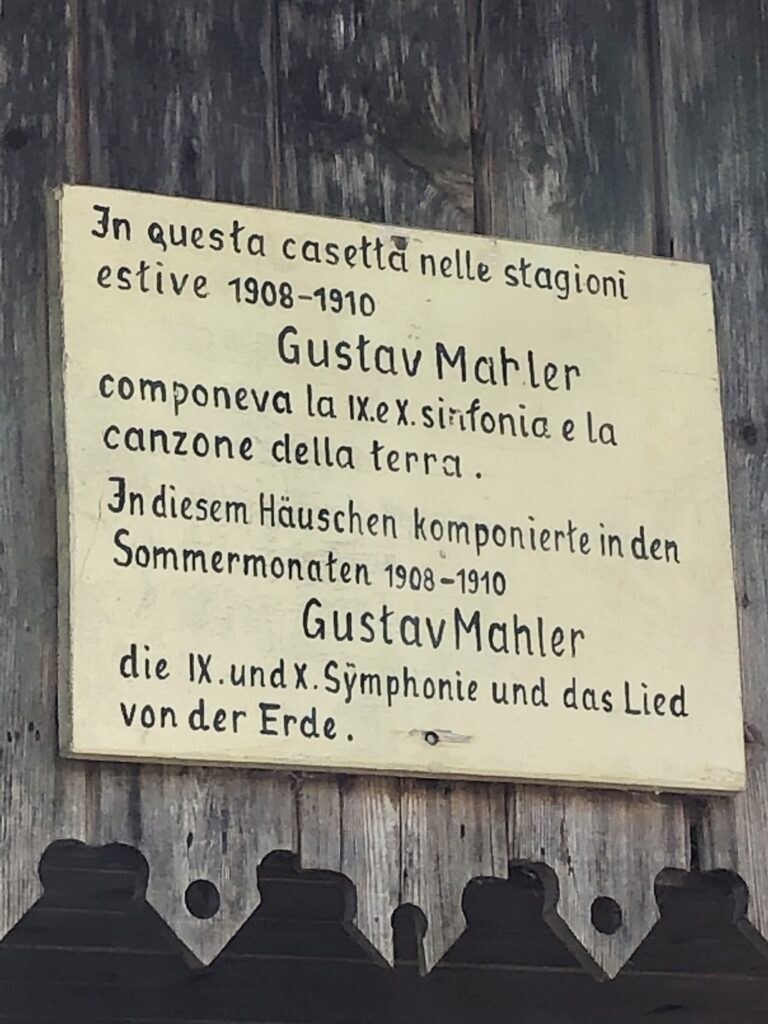

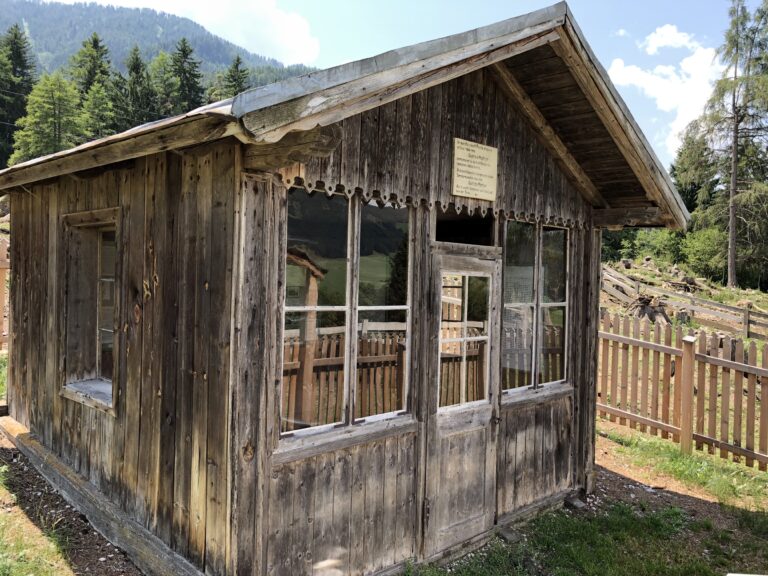

Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, the last he completed, occupies a singular place in the repertoire. Composed in 1908–1909 and premiered posthumously in Vienna in 1912 by Bruno Walter, more than a year after the composer’s death, it remains an enigma of farewell. Mahler would never hear this symphony, so often regarded as his final adieu to life. The expansive and intricate first movement, Andante comodo, seems haunted by a premonition of death: Mahler even marks one passage with the stark indication « Wie ein schwerer Kondukt » (« like a heavy funeral procession »). Alban Berg, profoundly shaken upon discovering the work, wrote that « the first movement is the most glorious thing Mahler ever composed. It expresses an unimaginable love of this earth, the longing to live on it in peace, to enjoy it wholly and deeply. »

The Ninth is often perceived as Mahler’s swan song, oscillating between a searing love for earthly life and an almost serene acceptance of death. Its final Adagio, fading gradually into silence, has been described as « ineffably tender« : a kind of mystical lullaby of farewell. And yet, it is a work of many faces: while the shadow of death looms large, the Ninth also serves as a radical laboratory of musical modernity. Its daring dissonances and unorthodox architecture anticipate the innovations of the Second Viennese School, prompting some to call it prophetic.

From its very first performances, the Ninth drew intense reactions. Some heard in it a sublime meditation on departure and transfiguration; others were disoriented by its bleakness and apparent fragmentation. A critic in 1912 spoke of its « sunset atmosphere », tinged with the farewell mood of Das Lied von der Erde; another noted that after the transformations of life, Mahler simply « says goodbye ». For the modern listener, aware that this is the composer’s last completed message, each performance bears a unique emotional charge. For conductors, the Ninth remains a formidable trial: « Reaching the end of this symphony is one of the most difficult tasks in the entire profession, » confessed Herbert von Karajan. To conduct those final pages, as the music gradually fades like a life ebbing away, is to brush the edge of emotional and spiritual abyss. Mahler himself was acutely aware of this transcendental challenge. Hence the oft-cited « curse of the Ninth » (after Beethoven, Schubert, and Bruckner, no great symphonist would survive his ninth…). This quasi-mystical aura continues to surround every performance of the work.

The Ninth and the Berlin Philharmonic: A Legendary Tradition

If Mahler’s Ninth Symphony occupies a mythical place in the repertoire, its history with the Berlin Philharmonic is no less prestigious. For a long time, Mahler’s music was seldom performed in Germany, and it was not until the 1960s that the prestigious Berlin ensemble began to devote itself seriously to it.

A historic milestone was set in January 1964: Sir John Barbirolli, the British guest conductor, led the Ninth Symphony in Berlin and delivered a recording that would soon become legendary. At the time, it was a remarkable event: the orchestra did not yet have a Mahlerian tradition in its blood, and it took Barbirolli’s passionate conviction to instil it. The Berlin musicians, it is said, were so deeply moved by his vision that they insisted on recording it, despite the exclusive recording contracts of the Karajan era. Barbirolli, not generally expected to be a Mahlerian of the first rank, achieved a masterstroke. His interpretation avoids both the scorching hysteria of Bernstein and the austere restraint of Klemperer, striking an ideal balance with tempi and dynamics of exemplary accuracy. The sincerity and warmth of this reading, captured in the sumptuous tonal palette of the Berliners, still make it an absolute benchmark. It was named EMI’s « Recording of the Century », and many critics continue to cite it as their desert-island Ninth.

During Herbert von Karajan’s long reign at the helm of the Berlin Philharmonic (1955–1989), Mahler remained somewhat marginal. It was only in the late 1970s that Karajan finally tackled the Ninth, and in unforgettable fashion. In 1982, he conducted it on several occasions: at a deeply moving concert in Salzburg in April, then again on tour in Berlin, Salzburg once more, and later that autumn in New York and Pasadena. These late interpretations left a profound mark on both conductor and audience. According to critic Richard Osborne, the Salzburg concert was so emotionally overwhelming that he had to cancel his dinner plans, unable to recover from the shock. Karajan himself confided: « I know: it was the same for me. That sort of thing only happens once in a lifetime. » Under the Austrian maestro’s baton, the Ninth became a threshold experience: a journey to the far edge of night, leaving listeners shaken. Karajan recorded the symphony both in studio (1980) and live (1982, Berlin Philharmonie), producing two readings of astonishing technical perfection, with a sound of almost otherworldly beauty, reflecting the aesthetic hedonism of the orchestra at that time. His approach sought a kind of transcendent purity, a « sound veil » achieved only after endless rehearsals, seventy hours for this work alone, he reportedly confessed. The result was a vision purged of all pathos. « There is immense beauty in the Ninth, » Karajan once said, « and a feeling of harmony with death. » Over the course of these performances, conductor and musicians reached a state of grace, particularly in the Salzburg finale, where, according to some, the orchestra played « as if life itself were burning out. » Drained by this confrontation with the absolute, Karajan resolved never to return to the work. His final performance of the Ninth, in Pasadena in October 1982, was followed by an unequivocal statement: « I was madly, madly invested in this symphony. And when it was done, and this is one of the very few pieces of which I say this, I would never dare touch it again. » The Mahler monument was now etched in the marble of his career: an emotional summit beyond which he chose not to venture. Of course, other recordings of other Mahler symphonies by Karajan exist, and all deserve rediscovery: the conductor’s affinity with the composer ran deeper than many had assumed.

In parallel, another great Mahlerian offered the Berliners a radically different and equally unforgettable vision: Leonard Bernstein. The American conductor, an impassioned advocate for Mahler, had never conducted the Berlin Philharmonic. The near-miraculous event took place in October 1979: invited as part of the city’s festival, Bernstein led two extraordinary performances of the Ninth Symphony, his only appearances with the Berliners.

The impact was seismic. Where Karajan exalted form and sonic beauty, Bernstein gave an incandescent, viscerally expressive Ninth, infused with humanism and fervour. The contrast between these two visions, the Apollonian and the Dionysian, has permanently enriched the Berlin tradition.

Bernstein’s interpretation, recorded live and later released by Deutsche Grammophon, was marked by emotional surges of rare intensity, wrenching crescendos, and interminably suspended silences. It is said that during the Adagio finale of one of these concerts, an audience member collapsed in tears, momentarily interrupting the musicians, an anecdote that speaks volumes about the extreme emotional tension of those legendary evenings.

Bernstein viewed Mahler as a spiritual brother, and his exalted approach to the Ninth, brimming with restrained tears and desperate lyricism, remains etched in the Philharmonic’s history.

Following Karajan, each of the orchestra’s successive music directors added their own stone to the Mahlerian edifice.

Claudio Abbado (music director from 1989 to 2002) made Mahler a cornerstone of the Berlin repertoire, bringing a new luminosity to the works, more transparent, chamber-like, and an eminently poetic sensitivity. His own recording of the Ninth with the Philharmonic strikes by its modest humanity and its luminous detailing, while his famous 1999 farewell concert with this same symphony was hailed for its spiritual intensity.

Sir Simon Rattle (2002–2018) continued this legacy, exploring every corner of the score with analytical precision and renewed breath, boldly accentuating the modernist contrasts of the symphony. Under his baton, the orchestra reached new heights of virtuosity and stylistic flexibility. His performances offered a Ninth in sharp hues, boldly structured, especially during a memorable 2011 tour when the finale left the Royal Albert Hall in tears and silent for long seconds.

Each great Berlin milestone in the Ninth has thus revealed a different facet of Mahler’s masterpiece: Barbirolli’s authentic depth, Karajan’s formal perfection and ecstatic surrender, Bernstein’s visceral passion, Abbado’s luminous poetry, Rattle’s razor-sharp reading…

Kirill Petrenko and the Ninth Symphony: the Challenge of a New Era

It is in the footsteps of these giants that Kirill Petrenko, current Chief Conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker, has now taken up the challenge of Mahler’s Ninth.

A Russian-born maestro trained in Austria, Petrenko assumed the musical directorship in Berlin in 2019, immediately commanding deep respect from both orchestra and public. Shunning the media spotlight, meticulous in rehearsal, he has established himself through the architectural clarity of his interpretations and his singular ability to galvanise the players from within. While his core repertoire has long encompassed opera and early 20th-century music, Petrenko has, in recent years, approached Mahler’s symphonies with a profoundly personal vision. Rather than follow in the footsteps of his illustrious predecessors, he brings a fresh, almost ascetic perspective to these emotionally searing pages. His guiding principle: « Reject gratuitous pathos, delve into the score’s essence, sculpt its sonic architecture. »

From his very first Mahler concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic, critics and listeners alike noted the surgical precision of his baton, his resolute rejection of sentimental overstatement. Petrenko prefers to foreground Mahler’s inherent modernity (the expressive violence, the sharply etched textures) rather than leaning into its emotional excesses. This approach was particularly striking in last year’s interpretation of the Seventh Symphony, where his febrile energy and insistence on clarity illuminated a thousand unsuspected details in the score, even if it meant unsettling familiar listening habits. His Mahler is a compelling synthesis: rigorous analysis (partly in the lineage of Rattle) combined with a restrained but simmering Dionysian intensity (occasionally recalling Bernstein’s electricity, yet channelled through a distinctly Germanic discipline).

Expectations were high, then, for his account of the Ninth in Lucerne with the Berlin Philharmonic. How would this understated conductor, all controlled gesture and quiet authority, navigate such a journey to the musical beyond? Would he favour raw emotion or relentless structure? The answer is given tonight at the KKL Konzertsaal in Lucerne: Kirill Petrenko reveals himself as the prophet of a vertiginous Ninth, majestic in its darkness, that deepens a long lineage with a singular voice.

Petrenko’s Ninth in Lucerne: A Mechanics of Vertigo

From the very first bars, the tone is set. A hesitant string tremor, that famous two-note motif pulsating like a weary heart, and the entry of the solo horn, slightly imprecise in its initial attack, the only minor technical flaw in an otherwise masterful evening. Mahler’s Ninth opens in Lucerne as if seen through a pane of glass: the sonic world appears shrouded in mist, distant, almost unreal. Petrenko establishes a dreamlike sense of displacement, as if life were being observed from the other side. Unlike so many interpretations that seek immediate emotion, the Russian conductor avoids all exaggerated pathos from the outset. His direction, fearsomely precise, brings out an implacable sonic architecture. One is struck by the organic coherence of the discourse: each motif is presented with clarity, each transition finely negotiated, so that this vast Andante comodo (more than twenty-five minutes long) seems to follow the relentless thread of a tragic thought. Petrenko exalts a kind of cold beauty: what dominates is not emotion, but the awareness of a universe inexorably coming apart. Everything breathes modernism in this first movement. The thematic meanderings at times take on expressionist, almost Schoenbergian overtones, so unvarnished are the dissonances as they erupt. One thinks of Klimt’s canvases or Kokoschka’s nightmares, Mahler’s era revisited through a merciless lens. An infernal clock seems to govern the ebb and flow of inner chaos: Petrenko draws forth the strata of this complex music with uncommon analytical boldness, as though dismantling the gears of a machine of fate. The dissonances lash, the crescendos are sculpted with a scalpel, the mechanism grinds forward, relentless. The conductor maintains a dry, nervy tension; it is not cold: it is dry and sharp, one might say burning in its aridity. Such a reading lends the pain that permeates this movement an abstract, almost theoretical quality. It is a suffering internalised, held at a distance, a meditation on misfortune, never a weeping lament.

And yet the flesh of the music vibrates nonetheless. The Berlin brass, flawlessly precise, impose a magnetic presence: their distant calls ring like trumpets from beyond, impeccably tuned yet tinged with a dark grain. Petrenko moulds this dense orchestral matter like a molten sonic paste. He spreads, layers, excavates harmonic strata, revealing the vertiginous depth of a world suspended at the brink of nothingness. The soloists are dreamlike, each emerging like a character in this spectral theatre: Emmanuel Pahud’s flute, for instance, unfolds evanescent arabesques, light as the breath of a fading memory. The balance between sections is sovereign, measured to the millimetre without stifling individual expressivity. In the final minutes of this first movement, the tension gradually subsides: the violins, in an exhausted murmur, converse with the flute exhaling its last notes, one thinks of the closing bars of Das Lied von der Erde, those farewells dwindling and fading, magnificently desolate, into silence. Here too, the progressive erasure leads to the pure and simple disappearance of sound. Petrenko lets the music vanish, matter-of-factly, almost resignedly. The silence that follows is abyssal. One realises then that, without ostentatious pathos, this interpretation has reached a staggering level of truth: it has shown us a world in the process of disappearing, with unflinching lucidity.

A complete change of scenery follows in the second movement, which bursts forth in an entirely different orchestral body. Mahler, after the vast panorama of the first movement, leads us into a grotesque Ländler, a deliberately unhinged Austrian country dance, nostalgic and ironic. Under Petrenko’s baton, this Ländler takes on even more Brucknerian contours: it lumbers forward, delightfully clumsy, like a surly bear, yet without excessive caricature. The conductor sets a welcome rhythmic sobriety, allowing the music to unfold its own irony. The strings emphasise the strong beats with the coarseness Mahler demanded (« Etwas täppisch und sehr derb, » notes the score: « somewhat clumsy and very crude »), while the winds offer trills and rustic motifs in a tone of false naivety. One imagines clogs dragging through wet earth: this scherzo feels like a village fête morphing into a ghostly sarabande. The clarinets sound rustic, the interventions of tuba and trombones bear a wry pungency, as if the orchestra were mocking itself. It is a dance of shadows that Petrenko orchestrates with consummate paradox: he organises chaos with clockmaker precision, while giving the illusion of a drunken farandole. There is a sense of contained jubilation, a perpetual wink. Petrenko seems to revel in this grotesque carnival, taming the Dionysian chaos under absolute Apollonian control. Everything is present in the music: each acceleration, each grating violin glissando, each rhythmic accent is meticulously placed, and yet the sense of derision emerges fully. The conductor even moves his shoulders overtly at times, Bernstein-style, silently underscoring the mise en abyme of a world veering off course, smiling at itself. This nuanced reading avoids the heaviness this movement can sometimes carry: Petrenko renders it both raucous and spectral, with a satirical distance that hits the mark.

But it is the third movement, the terrifying Rondo-Burleske, that strikes the heart and leaves the listener pinned to their seat. Petrenko and his musicians are nothing short of astonishing. Rarely has one heard a Rondo-Burleske of such biting dryness, such febrile urgency. It becomes, quite literally, a race into the abyss. Petrenko approaches this movement as a desperate flight, an infernal gallop where the music seems to try to outrun its own fate. The tempo is breakneck, yet never out of control; the orchestra follows with diabolical virtuosity. The fugal entries of the various themes are as sharp as blades. The winds sneer, flutes and clarinets launch biting, mocking motifs, the brass jeer with a sarcasm bordering on the vulgar (Mahler indicates Sehr trotzig, « very defiant », and that is exactly how the trumpets and trombones play: with insolence). The rhythms run wild, the asymmetric signatures and constant changes of metre are navigated with Olympian precision by Petrenko, so that the chaos remains always legible. There is no space left, no respite: the music chases the listener like a hound on the hunt. It is a pursuit, a merciless hunt, punctuated by grating laughter and sonic grimaces. One hears a black sarcasm, as if Mahler were mocking the futility of all things before the end of the world. Suddenly, at the climax of this frenzied race, as the universe seems to collapse on all sides, the harps enter, two of them, plucking broken, decelerated chords. Petrenko brings out this motif with chilling clarity: it embodies the disintegration, the collapse of the sonic world. It feels as though, amid the frenzy, the floor beneath our feet is cracking. This passage, barely ten bars long, chills the blood by its stark contrast to the previous fury. The conductor imperceptibly stretches the tempo here, suspending time in a moment of dramatic slow motion. Then the chase resumes, more frantic still, only to halt abruptly in a dissonant cry. The tension reached in this Rondo-Burleske becomes almost physical, painful, the audience seems to hold its breath before this precipice of the world’s end. One must salute the orchestra’s absolute mastery: under Petrenko’s firm guidance, they achieve a genuine tour de force of musical vertigo. Every section is pushed to the limits of its virtuosity, and all respond without a single flaw. The violins, led by Noah Bendix-Balgley, are beyond praise in their commitment. When the movement ends suddenly, in a scalding burst like a hammer blow, the hall remains frozen, stunned by an apocalyptic storm.

After such cataclysm, the final Adagio comes as a long exhalation… but make no mistake: it offers no consolation. In Petrenko’s hands, this Adagio never lapses into the tender or lachrymose serenity sometimes heard. He approaches this last movement with almost severe rigour, proceeding note by note like the ticking of a countdown. The opening bars are detached, distant, the cellos state the initial chorale calmly, without outpouring. But it is only a surface impression: little by little, another order of emotion surfaces, one that is more metaphysical. Petrenko counts the pulses of a dying heart. The violins sing the main theme, that broad melody which under other batons might bring tears, in his, it is rendered with restraint, with extreme modesty. They brush the abyss with the tip of the bow. The effect is all the more poignant: it is as if the entire orchestra were gazing into the void, stoic. This is not romantic sorrow, it is a portrait of nothingness. One witnesses the progressive rarefaction of musical oxygen. The sound grows ever more stripped-down, the dynamics inexorably diminish. The air is cut in the hall, so palpable is the tension even in this extreme deceleration. Petrenko seeks no grand arc, no ascent towards light, unlike other versions where the Adagio turns into a redemptive apotheosis, here, there is no redemption, no light at the end of the tunnel. Only a long ritardando, a deliberate slowing of all sonic life. The same harps that signalled collapse in the previous movement return here pianissimo, spinning out delicate harmonies like fine threads: they sound like the ticking of a distant clock… one cannot help but think of Shostakovich’s future Symphony No. 15, whose enigmatic finale will also evoke a clock winding down. Tick… tock… time runs out. A memory unravels; each instrument falls silent in turn, like stars vanishing from the sonic firmament. The violas exhale a final countermelody, then only a few violin filaments remain, and the flute’s ultimate breath… The world fades away, gently, inexorably.

The silence following the final note is of abyssal depth. Petrenko holds his arms aloft for a long time, motionless, preventing any premature applause. In this stillness, one senses the audience resounding with silence, a silence heavy with meaning. The triumphant, fervent ovation is not long in coming. Despite the restraint and rigour of the interpretation, the emotional impact is immense. One leaves the concert with a heavy heart, short of breath. This is not a symphony that makes one sob openly; in that regard, Petrenko’s interpretation stands at the opposite pole from the unforgettable concerts of Claudio Abbado. The listener is struck instead by the lightning of this naked truth, this unflinching beauty. One is left stunned, transfixed, the heart pounding, the body battered.

Mahler, under Petrenko’s baton, became this evening an oracle speaking to us from the beyond, not with pathos, but with implacable precision. And the Berlin Philharmonic, that formidable instrument of obsidian, hewn from shadow and fire, served as the vehicle of this musical prophecy. On this Lucerne evening, death shed no tears. It bore precision. Verticality. A beauty that made the soul tremble. That vertigo, made of cold and terrifying, beauty will haunt us for a long time. And one cannot help but think, upon leaving the hall into the Swiss night, that Mahler himself would surely have been shaken by what he heard this evening, somewhere… on the other side of the shore.