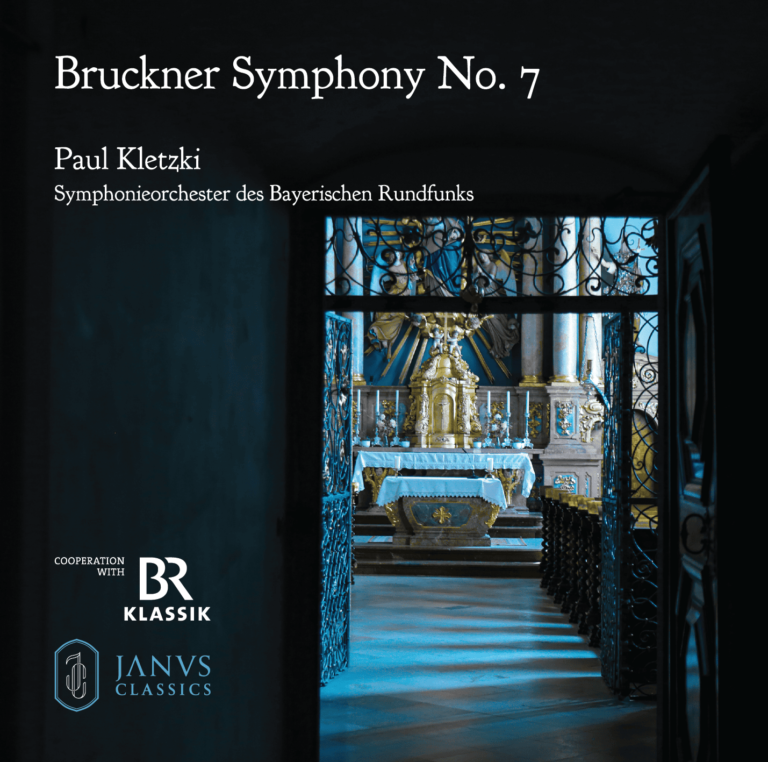

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896): Symphony No. 7 in E Major, WAB 107 (1885 revision, Leopold Nowak edition, 1954)

Orchestra: Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO)

Conductor: Paul Kletzki

Recording: Live, January 25, 1973 – Herkulessaal, Munich

Label: Janus Classics – JACL-5

Total Duration: 63’45’’

Remastering: 32-bit Spectral Remastering

Booklet: English & Japanese, includes rare photographs

Paul Kletzki’s Lost Bruckner 7: A Radiant Rediscovery

Paul Kletzki’s only recorded Bruckner 7th, captured live in Munich in 1973 with the BRSO, is a radiant rediscovery. Janus Classics’ 32-bit remastering brings new clarity to this luminous and fluid interpretation, making it an essential addition to the Bruckner discography.

Paul Kletzki (1900–1973) remains one of those conductors whose name appears sporadically in the discography yet always attached to interpretive gems. Though widely respected during his lifetime, his legacy has faded compared to his more frequently reissued contemporaries. Best known for his Mahler, Tchaikovsky, and a luminous Rachmaninoff Second Symphony, he left behind only one documented Bruckner performance: this live Seventh Symphony from Munich’s Herkulessaal, recorded mere months before his passing.

That this rarity has been resurrected by Janus Classics is a major event. Their 32-bit Spectral Remastering breathes new life into the original recording, bringing an unprecedented clarity that preserves the natural acoustics while revealing fine details previously lost in the analog limitations of the time. Kletzki’s Bruckner, light on its feet yet profound, finally emerges in its full splendor, free of any sonic murkiness that could have obscured his distinctive interpretive choices. The accompanying booklet (in English and Japanese) adds further value with detailed notes and rare archival photographs, reinforcing this as a true archival rediscovery rather than a mere reissue.

Captured live on January 25, 1973, this performance shares the evening with Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3, played by Ilan Rogoff. This programming is revealing: Kletzki approaches Bruckner not through the weight of late Romanticism but through the structural clarity of Beethoven and the melodic expansiveness of Schubert. His Seventh is neither an immovable cathedral of sound nor a sweeping, grandiose edifice; instead, it breathes, it moves, it unfolds with a natural inevitability.

When comparing Kletzki’s version with contemporaneous recordings by Böhm (1976, Vienna Philharmonic) and Karajan (1975, Berlin Philharmonic), its uniqueness becomes even more apparent. While the overall timings are similar, the differences in conception are striking. Karajan sculpts Bruckner’s architecture with monumental precision, while Böhm lingers over the Adagio, stretching its grandeur. Kletzki, by contrast, achieves transparency and momentum, maintaining depth without ever dragging the phrasing into excessive solemnity. His Scherzo is energetic and incisive yet retains a sense of effortless propulsion. The Adagio, a movement often treated as a meditation on eternity, retains its spiritual depth but never loses its forward motion.

A particularly striking moment occurs around the 18-minute mark of the first movement, where Kletzki introduces a slight but significant slowing of tempo. It is a moment of near-suspension, a breath before the coda, almost as if the music itself were contemplating the vastness of its own structure. Given that this was Kletzki’s final recorded performance, this passage takes on a profound significance—less an indulgence, more a poignant acknowledgment of the symphony’s sheer scale and emotional depth.

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra is in superb form, an ideal partner for Kletzki’s vision. Each section is given space to shine, but the brass, particularly the Wagner tubas, stand out for their noble restraint. Instead of overwhelming the texture, they blend seamlessly into the symphony’s harmonic fabric, rising in grandeur when needed but never imposing an artificial weight. The woodwinds bring exceptional clarity, their phrasing natural and fluid, particularly in the Scherzo, where their interplay with the strings evokes something almost Schubertian in character. The strings maintain cohesion and warmth, providing a solid foundation without thickening the orchestral sound unnecessarily. Thanks to the acoustic properties of the Herkulessaal, enhanced further by the remastering, every section of the orchestra finds its rightful place in the soundscape.

One of the greatest achievements of this release is its 32-bit Spectral Remastering, which goes beyond simple noise reduction. By isolating and enhancing frequency layers, it restores a level of dynamic contrast and instrumental separation that brings this 1973 performance into a new era. The brass has a burnished glow, the strings retain their warmth, and the woodwinds shine with crystalline clarity. This is not merely a historical document; it is a fully immersive listening experience that places the audience right in the heart of the Herkulessaal.

Paul Kletzki’s final recording is no longer a footnote in Bruckner discography—it stands as an essential alternative to the dominant interpretations of its era. Thanks to Janus Classics, this hidden gem is finally given the recognition it deserves, allowing us to experience Bruckner’s Seventh in a way that is both deeply human and spiritually transcendent.

Interpretation: ★★★★★ – A luminous, fluid, and transparent Bruckner, free of excess weight yet deeply structured.

Sound Quality: ★★★★☆ – 32-bit remastering brings clarity and depth, though some analog limitations remain.

Booklet & Edition: ★★★★★ – Richly detailed, with rare photos and insightful notes.

Historical Significance: ★★★★★ – Kletzki’s only recorded Bruckner 7, finally restored and essential for collectors.

Overall Rating: 4.8 / 5 – A must-hear rediscovery, revealing a unique and deeply human vision of Bruckner.